AI-generated summary

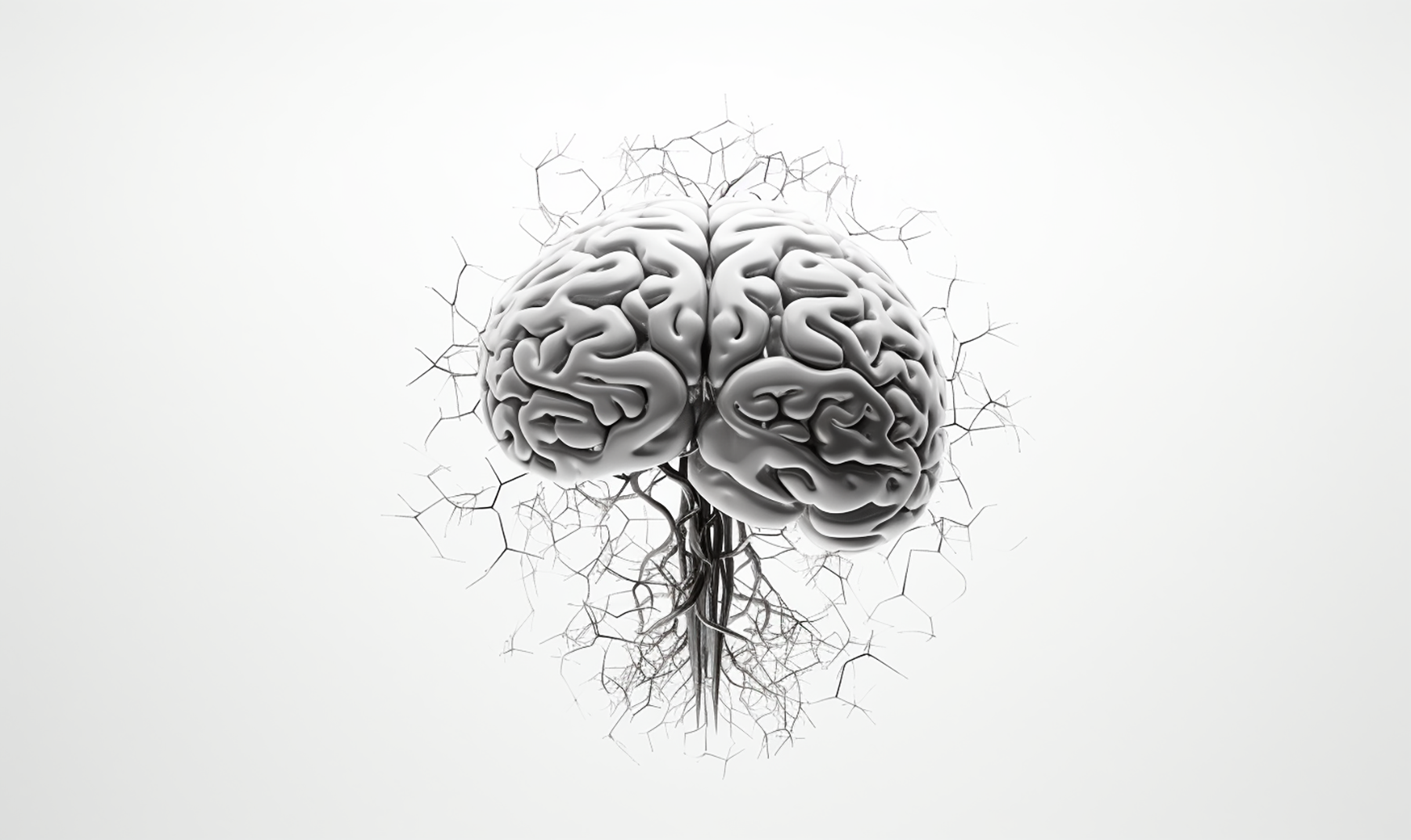

Neurotechnology refers to a broad set of tools and methods used to record, measure, and influence brain activity, including neuroimaging, brain implants, and brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). These technologies offer significant medical benefits, such as restoring functions lost to nerve damage or treating neurological disorders like Parkinson’s disease and severe depression. Beyond medicine, neurodevices are increasingly used by healthy individuals for entertainment, training, and commercial purposes, including neuromarketing to predict consumer preferences. However, the potential to enhance cognition and influence decision-making raises ethical concerns, prompting calls for new legal protections known as “neurorights.” Coined by academics Roberto Adorno and Marcello Ienca, neurorights encompass four key categories: cognitive freedom, mental privacy, mental integrity, and psychological continuity. These rights aim to safeguard individuals from unauthorized access to neural data, harmful manipulation of mental activity, and disruptions to personal identity caused by neurotechnology.

As neurotechnology advances and becomes more accessible, including through AI-enhanced BCIs, regulating its use is crucial to ensure ethical and socially responsible innovation. International bodies like UNESCO emphasize the importance of balancing medical benefits against risks and warn against non-medical applications without proven safety or efficacy. Issues such as brain data privacy, neurodiscrimination, and threats to personal integrity highlight the challenges to human rights posed by these technologies. Some countries, including Chile and Spain, have begun enshrining neurorights in law to protect citizens. Looking ahead, maintaining public trust will require clear regulations, robust data protection infrastructures, and widespread public awareness to manage the ethical implications of brain-machine interfaces and neurotechnology.

Advances in neurotechnology and its potential to 'manipulate' brain activity open up new scenarios that challenge the meaning of the human being.

Neurotechnology is an ‘umbrella’ term that encompasses all those tools and methods that allow us to record, measure and/or influence brain signals. This includes emerging technologies such as neuroimaging, with which to visualize the areas of the brain corresponding to thoughts or actions; transcranial magnetic neurostimulation, capable of modulating the mind; microchip brain implants, which can stimulate thoughts and actions, and the interface to connect the brain and the machine.

The benefits derived from the development of neurotechnology are evident in the medical field: for example, ‘jumping’ damaged nerve circuits and restoring the function derived from them (as in the case of paralysis due to spinal cord trauma), as well as modulating/reprogramming those brain circuits responsible for motor and/or cognitive symptoms (such as Parkinson’s disease or severe depression).

But there are also numerous neurodevices used by healthy subjects, for entertainment, training or commercial purposes: caps or headphones that allow simple operations to be carried out by taking advantage of the intensity of brain waves, as in some video games. Neuromarketing, on the other hand, applies neurotechnology techniques to predict consumer preferences.

Both potential, as well as the real possibility of improving cognitive abilities and influencing/conditioning our decision-making capacity or behaviors, can hide some dark sides. That is why the neuroscientific community (and not only) questions the need to equip itself with an ethical and legal regulation that is based on an initial question: do we need to codify and protect new rights, the so-called ‘neurorights’ of the person?

The expression ‘neurorights’ was coined by academics Roberto Adorno and Marcello Ienca with the aim of defining an emerging category of human rights related to the mental and neurocognitive sphere. The idea is inspired precisely by the development of neurotechnologies and sophisticated brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), potentially capable of influencing human thinking and action.

The theory has identified four categories of neurorights: the right to cognitive freedom, the right to mental privacy, the right to mental integrity, and the right to psychological continuity. The right to mental privacy should allow individuals to protect neural information from unwanted access and control, especially with respect to information processed below the threshold of conscious perception; The right to psychological continuity would preserve the identity of people and the continuity of their mental life in the face of unwanted alterations by third parties.

Then there is the right to mental integrity (already recognized by art. 3 CDFEU, through its extension), which should be understood as a useful right to protect against illicit and harmful manipulation of mental activity as a result of the improper use of neuroscience technologies. Finally, the right to cognitive freedom should protect the fundamental freedom of individuals to make free and competent decisions about the use of BCIs.

Today there are already numerous techniques for extracting and analyzing neural data. If at first this field was closely linked to the medical sector, over time the analysis of neural data could also be possible by unqualified subjects, through the use of specific and easier to use BCIs, especially thanks to the development of Artificial Intelligence.

For this reason, equipping oneself in time with adequate tools to regulate the development and use of neurotechnology represents a fundamental step towards achieving truly sustainable innovation from an ethical and social point of view. As argues the professor John Tasioulas, Quain Professor of Jurisprudence at University College London, said: “We should not think about everything that AI will be able to do, but about what we are going to allow it to do”.

Currently, various international organizations already converge on a series of standards in terms of security and privacy that guarantee the use of neurotechnologies and the ‘brain‘ data that can be acquired/analyzed with them in full harmony with the rights of the person. However, these are recommendations that are not currently legally binding.

The document of the International Bioethics Committee of UNESCO, Report on the ethical aspects of neurotechnologies, raises some ethical questions. The Committee considers that technologies are always justified in medicine if the expected benefits are adequate compared to the risks, but are illegitimate or largely problematic if used in non-medical settings, where neither safety nor efficacy has been demonstrated.

Some risks are also highlighted, including that of the integrity of the person; the risk of finding ‘brain data’, that is, inferring private information without the subject being aware of it; the risk of ‘neurodiscrimination’ based on the characteristics of the brain or on information extracted from mental activity. The UNESCO document stresses that new technologies, on these points, challenge human rights.

In April 2021, the Senate of the Republic of Chile approved a constitutional reform law that defines psychic integrity as a fundamental human right, and a law that protects neurorights and applies existing medical ethics to the use of neurotechnologies. The Spanish government is also taking stock of the situation: the Secretary of State for Artificial Intelligence has published a Digital Bill of Rights that incorporates neurorights as part of the citizens’ rights of the new digital era.

In the not-too-distant future when brain-machine interface is becoming more widespread, there will be a growing need to maintain trust in the exchange of data between citizens. This can be achieved through clear rules for the collection and secondary use of data, new digital infrastructures for data protection, greater collective awareness and the thoughtful application of neurorights.