AI-generated summary

Artificial intelligence (AI) is advancing rapidly, raising enthusiasm about its potential but also significant concerns about its real energy impact. Vaclav Smil, an expert in energy and technology, highlights in a Future Trends Forum webinar that the growth of AI and its data centers demands constant, massive electricity consumption, which exerts pressure on power grids, cooling systems, materials, and water resources. Smil stresses that the global energy system is vast and slow to change, heavily reliant on fossil fuels that provide continuous power—something intermittent renewables cannot yet fully replace due to lack of large-scale storage. AI exacerbates existing energy demands rather than altering the foundational dynamics. The anticipated expansion of data centers, particularly in the U.S., will require tens of gigawatts of new capacity, straining local infrastructure and resources. Solutions like gas turbines and nuclear small modular reactors face practical, regulatory, and social obstacles, making rapid scaling unrealistic. Similarly, nuclear fusion, often touted as a future fix, remains decades away from commercial viability.

Smil argues that energy challenges lie less in scarcity and more in consumption patterns and political choices. Europe’s energy “security” issues stem from policy and market dynamics, not absolute shortages. The greatest opportunity to address energy and environmental problems is in reducing waste and consumption—such as cutting food waste, downsizing vehicles, improving building efficiency, and curbing energy-intensive behaviors like frequent flying. Technological fixes alone are insufficient without structural changes in investment, policy, and societal behavior. Ultimately, Smil’s clear message is that the solution is not to produce more energy but to need less, emphasizing efficiency and responsible consumption as the most effective paths forward.

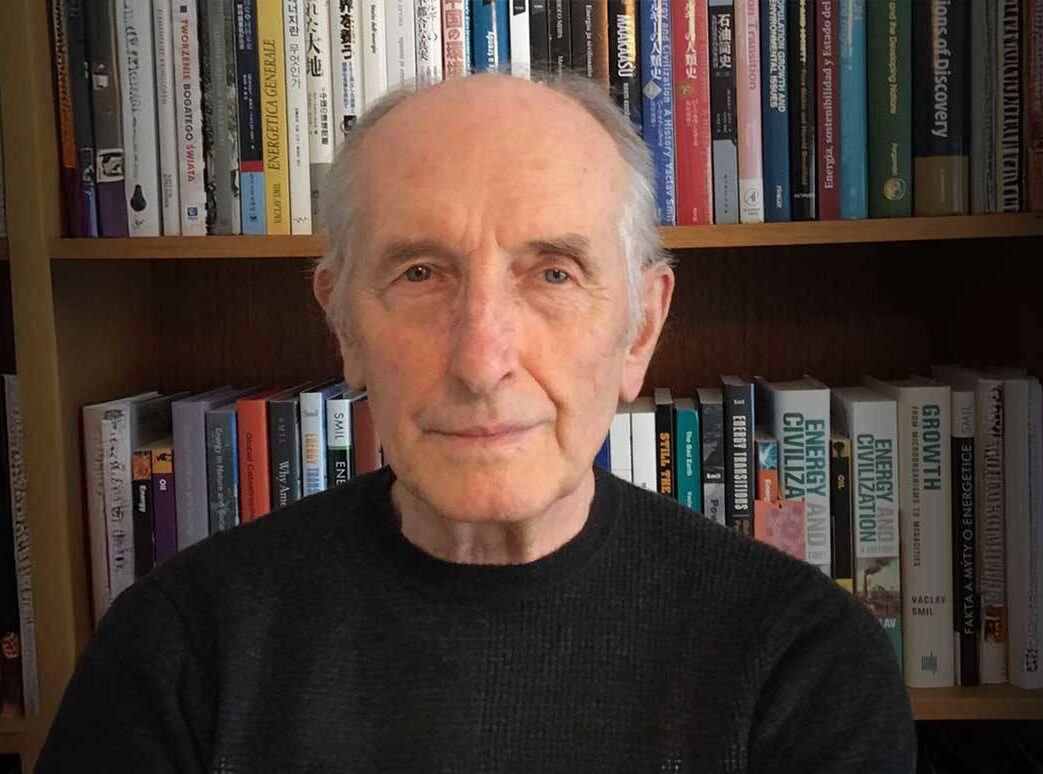

Vaclav Smil puts numbers on the energy impact of AI and data centers, and explains why scale and physics matter more than hype.

Artificial intelligence is advancing at great speed. So does the enthusiasm that surrounds her. But what happens when that hype is confronted with the physics, scale, and real limits of the energy system?

In this webinar of the Future Trends Forum, Vaclav Smil, one of the world’s leading experts in energy and technology, puts figures where others make promises. With his usual approach – data, thermodynamics, and a sense of scale – Smil analyzes the real energy impact of the rise of AI and the data centers that sustain it: constant electricity consumption, pressure on networks, massive needs for cooling, materials, and water, and deployment timelines that are not accelerated by headlines.

In conversation with Frances Sellers, moderator of the Future Trends Forum, Smil insists that thermodynamics, power density and the inertia of the energy system limit what can be done in the short and medium term. Faced with the promises of accelerated decarbonization and simultaneous digital growth, his diagnosis is clear: without deep structural changes and uncomfortable decisions in investment, public policy and business strategy, the expansion of AI will be supported – like the rest of the system – by a growing consumption of fossil energy.

If you want to watch the webinar, here it is: Vaclav Smil: the energy reality behind the great promises of AI

No energy transition (yet): a system too big to move fast

To understand the energy impact of AI, we must start with the real context of the global energy system. And that context, Vaclav Smil recalls, is that of a huge, inertial system that is extraordinarily slow to transform.

On a global scale, we are talking about billions of tons of coal, more than four billion tons of oil, trillions of cubic meters of natural gas and tens of petawatt hours of electricity generated each year. A system of that size doesn’t work like a Silicon Valley startup. It cannot be “broken and remade” in a few years. It changes, yes, but it does so in decades.

From this perspective, Smil is categorical: there has not been a global energy transition. Never. We use more fossil fuels today than at any time in history, even though at the same time we produce more solar and wind electricity than ever before. Renewables are not replacing fossil fuels; are joining them. That is not a transition, but an expansion of the total energy system.

The result is clear in the data. CO₂ concentrations in the atmosphere continue to increase year after year, with reliable measurements made far from major pollution hotspots. In 2023, around 427 parts per million were reached, a new all-time high. Consumption of coal, oil and gas also continues to grow, with coal in China and India particularly high and a new record in natural gas. All three fossil fuels are advancing at the same time.

This persistence is no coincidence. Coal remains a centerpiece of the global electricity system for one simple reason: it provides constant electricity. A thermal power plant can operate without interruption. Solar and wind power do not. The difference between intermittent and continuous sources is critical in a society that demands electricity 24 hours a day. Without mass storage – which does not exist today on the necessary scale – renewables alone cannot cover that demand.

In addition, the demand for electricity is growing faster than that of any fuel. It grows for structural reasons: population increase, industrialization, urbanization, air conditioning in hot countries. AI and data centers don’t change this trend: they intensify it. They are the latest factor added to an underlying dynamic that has been going on for decades.

That’s the real starting point. A global energy system that continues to grow, dominated by fossil fuels, with accelerating electricity demand and with physical limits that cannot be eliminated with optimistic narratives.

AI as an accelerator: tens of gigawatts concentrated in very few places

Once the starting point of the energy system is understood, the potential impact of AI is measured in speed and intensity, not substitution. And here comes the first big unknown: we don’t know how fast it will grow.

As Vaclav Smil points out, we can make estimates one or two years ahead, but five years later we are already entering highly speculative territory. Even so, forecasts proliferate. Especially in the United States, where a large part of the deployment of data centers associated with generative AI is concentrated.

The figures speak for themselves. Between now and 2030, the most cited scenarios point to the need to add around 50 gigawatts of new electrical capacity in the U.S. alone. To put it in perspective: one gigawatt is roughly equivalent to the constant consumption of a city of one million inhabitants in a rich country. Fifty gigawatts therefore means adding at once to the electricity consumption of 50 cities of that size.

On a global scale, estimates double: around 100 gigawatts additional in a few years. It is an almost unprecedented expansion in such a short time. And the problem is not only the magnitude, but the concentration.

Data centers are not evenly distributed. They are grouped near the major economic centers or areas with access to available energy and land. The result is an extremely unequal distribution: some territories will barely notice the impact, while others will concentrate a disproportionate share of the new demand. In the United States, regions such as the East Coast already bear a significant burden, with direct effects on local power grids and access to water for cooling.

This concentration amplifies all problems. More pressure on local networks, greater competition for water resources, territorial tensions and a foreseeable social rejection of the deployment of energy and data infrastructures. Added to this is a structural weakness of the U.S. system: the absence of a truly national electricity grid and the slow construction of new generation and transmission infrastructure.

Smil does not hide the contrast. While China has expanded its electricity capacity at a rapid pace over the past two decades, the United States is moving much more slowly. If current data center expansion plans are fully executed, the impact on the U.S. power system would be profound and difficult to manage.

In this context, AI is not an isolated problem or a simple increase in demand. It is a multiplier of tensions on a system already stretched to the limit, and its actual deployment may be even more complex than the aggregate figures suggest.

Networks, Cooling and Reactors: Why There Are No Quick Fixes

If the challenge is already enormous in terms of electrical capacity, the problem becomes more complicated when you go down to the terrain of the real infrastructure: networks, cooling, materials and technologies available here and now.

As Vaclav Smil emphasizes, the magnitude of the new demand forces us to look for solutions on multiple fronts. Neither wind nor solar alone can sustain an increase of tens of gigawatts: they are intermittent sources and there is no storage capacity at the necessary scale. For this reason, the debate inevitably turns to other options.

Gas turbines appear as the most immediate solution. They are mature technologies, manufacturable on request, scalable from a few megawatts to about a gigawatt, and installable in months. But even this route has obvious limits: there is not enough gas or operating margin to absorb such rapid growth in demand without additional stresses.

Hence the renewed interest in nuclear power, a technology that for decades has been politically blocked in the United States and Europe. The argument is well known: if you need an additional 50 or 100 gigawatts, why not turn to small modular reactors (SMRs)?

Here Smil is especially forceful. Today, in the Western world, not a single SMR operates commercially. Next year, either. And not because of a technical limitation. We know how to build and operate nuclear reactors: France gets more than 70% of its electricity from them; the United States, more than 20%; on a global scale, around 12%. The problem is not the “how,” but how many and how fast.

The arithmetic is devastating. If each SMR contributes in the order of 50 megawatts, covering an increase of 50 gigawatts would require thousands of new reactors by 2030. Going from zero to thousands in less than a decade, going through regulatory processes that last years and overcoming societal resistance to the deployment of reactors near residential areas, is not a realistic scenario.

In addition, data centers are not located in remote deserts, but on the outskirts of large cities, next to residential areas. The question is not just whether a reactor can be built, but whether anyone wants one “on the other side of the fence.” Added to this is the explicit opposition of countries such as Germany, which have closed the door to nuclear even in this new context.

The pattern repeats itself. Ambitious announcements, schedules that are delayed year after year and a persistent gap between technological hype and engineering reality. Smil compares it to other hyper-media projects that never materialize: promises that ignore times, permissions, materials and social acceptance.

In the case of AI and data centers, the conclusion is uncomfortable but clear: there is no miracle technology capable of absorbing this demand in a few years. The constraints are not conceptual, but physical, regulatory, and social. And those are not accelerated with enthusiasm or headlines.

Nuclear fusion: the perpetually deferred promise

When the energy debate enters more speculative territory, nuclear fusion often appears as the great clean, safe and definitive promise. For Vaclav Smil, it’s the perfect example of tech hype disconnected from real deadlines.

Their position is unequivocal. If I had to bet money, I would do it – with all caution – on nuclear fission and nothing on fusion. Not because the latter is impossible in principle, but because it has been installed in the same temporary place for decades: “in ten years’ time”. A pattern that Smil analyzes in depth in his book Invention and Innovation, where he dedicates an entire chapter to explaining why fusion always seems close and never arrives.

The recent enthusiasm is supported by two much-cited milestones: the ignition experiment at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in 2022 and the proliferation of startups promising compact and fast fusion reactors. Smil asks to separate headlines from facts. The Livermore experiment did not result in a net positive energy balance at the scale of the entire system, but rather a highly localized and highly technical result that does not change the actual state of the technology.

The best thermometer, he argues, is not startups, but large international projects. The paradigmatic case is ITER, the multinational consortium that brings together some of the best scientific capabilities in the world. After decades of work and tens of billions of dollars, its timetable continues to shift. The full operation is between 2035 and 2040, and the realistic commercial horizon does not arrive before 2045 or 2050.

That’s the pace when more than a dozen countries with nearly unlimited resources work together. To think that small private companies can solve the enormous technical challenges of fusion in a few years – confinement, materials, stability, energy conversion – is, for Smil, a financial illusion rather than a technological roadmap.

Comparison with other failed ads is inevitable. Promises that ignore engineering complexity, validation times, and the difference between demonstrating a physical principle and operating a reliable energy system on a large scale. Faced with the urgency posed by the growth of AI and data centers in this decade, the merger does not play on the same time board.

The conclusion is straightforward: fusion will not solve the energy problems associated with AI in 2030. It’s not even close. Perhaps it will be relevant in the middle of the century.

Energy security: not a problem of scarcity, but of price and priorities

The war in Ukraine reopened an old fear in Europe: energy dependence. But for Vaclav Smil, that fear is misfocused. After more than six decades analysing energy systems, his diagnosis is straightforward: there is no global energy security problem.

Smil distinguishes between political narrative and market reality. Europe has not stopped importing Russian energy altogether — it still buys liquefied natural gas — but it has replaced much of its oil and gas with supplies from Norway, the United States and other exporters. And it has done so without facing structural shortages.

The reason is simple: there is plenty of energy in the global market. Oil and gas supply is ample, with new capacities coming into production and a record volume of LNG available. Countries such as the United States, Canada, Qatar, Nigeria or Australia are willing to sell. Even new geographies, such as Guyana, aim to become large producers in a very short time. The message is clear: if you have money, you can buy energy.

From this perspective, Smil dismantles one of the most repeated assumptions in Europe. Germany does not need more energy to ensure its security. In fact, its electricity consumption has fallen recently, reflecting a deeper industrial stagnation. The problem is not access to energy, but the health of its productive base.

The comparison with China is revealing. The rise of the Chinese economy in recent decades would have been impossible without massive oil and gas imports. And yet, it was never a real obstacle. If a country of 1.4 billion people was able to secure its energy supply on the global market, there is no structural reason why an economy like Germany’s could not.

That is why Smil is categorical: Europe confuses energy security with military security. The first is resolved with contracts, infrastructures and payment capacity. The second is an entirely different problem. In addition, the current context is far from that of the great energy crises of the past. Oil and gas prices are not at record highs and energy is, in relative terms, as affordable as at many times in the past.

The conclusion is once again uncomfortable. We are not living in an era of global energy scarcity. We live in an era of difficult political decisions, assumed dependence on the international market, and narratives that exaggerate energy risk while ignoring other, much more critical structural factors.

The greatest energy resource is the one we waste

When talking about energy costs and carbon footprint, the focus is usually on which new sources to deploy. For Vaclav Smil, this approach avoids the main problem. The greatest margin for action is not in producing more energy, but in using much less.

Smil insists that advanced societies are structurally designed to waste energy on a large scale, and that this fact is ignored because it is politically uncomfortable. Changing the behavior of millions of people is much more difficult than building new plants or infrastructure. For this reason, it is almost never attempted.

The most striking example is the food system. Producing, processing, transporting, refrigerating and cooking food consumes around 30% of the world’s energy. It is an indispensable use. The problem comes later: about 40% of that food is wasted. Energy, materials and labour are lost because, in rich economies, food is cheap. When families in Europe spent 50 or 60% of their income on food, almost nothing was thrown away. Today, with an expenditure of 10–15%, waste has normalized.

The pattern is repeated in other areas. SUV vehicles, non-existent before the mid-1980s, have become the standard in many markets. They are getting bigger and heavier – up to 40% more than decades ago – without responding to a real need. More mass means more energy consumption, always.

Something similar happens in buildings. Simple, mature solutions such as triple windows reduce energy losses by 30 to 40%. However, in the United States, only 2% of households use them. In Canada, less than 20%. Only in countries such as Sweden is its adoption in the majority. The technology exists, it is effective and it is proven. It simply does not unfold.

Added to this is long-distance tourism, one of the most energy-intensive forms of consumption. Smil underlines a European paradox: there is a demand for greater climate awareness than in North America, but people fly much farther and more frequently. Before the pandemic, Germany spent more on international tourism than the United States, despite having a population four times smaller. Flying is extraordinarily energy-intensive, but it rarely enters the debate.

From this point of view, the question “how do we produce more clean energy?” loses its meaning. The most effective solution is not to need that energy. Not consuming it automatically avoids any environmental impact. All sources, including renewables, have material, territorial and geopolitical costs. Solar panels must be replaced every 20 or 25 years, and their production is now heavily concentrated in China, which generates new dependencies.

Smil has no illusions about the change of course. Public policies rarely attack consumption because they clash with the dominant ethos of Western societies: to consume more. Reducing demand, traveling less, driving lighter vehicles or wasting less food does not generate electoral enthusiasm. For this reason, technical solutions are sought that allow us to continue consuming the same or more.

The result is a vicious circle: energy is wasted on a large scale and then the question of how to produce even more. For Smil, this approach is not only inefficient. It is profoundly irrational.

Q Global Scale, AI, and Uncomfortable Decisions

Does it really matter that the U.S. pulls back from climate commitments?

In global terms, very little. The growth in coal, oil and gas consumption is no longer marked by the West, but by Asia. China and India continue to increase their use of coal because they need constant electricity to industrialize and for a population that demands air conditioning, transportation, and basic goods.

Even if Europe were to stop consuming coal altogether, global consumption would continue to grow as long as Asia and Africa did. And when the so-called peak fossil fuels arrives, there will not be a collapse, but a slow and generational decline. The scale of the system does not allow for sudden changes.

How much of AI’s energy growth is inevitable, and how much is optional?

Today’s forecasts are based on today’s technological efficiency, but electronics are always improving. Byte, training, or inference processing will be more efficient in five or ten years. How much, we don’t know.

In addition, AI is in an early phase of hype. As happened with personal computers or the Internet, total transformations are promised that later turn out to be partial. We do not know which uses will survive or which will prove dispensable. For this reason, Smil insists on not linearly extrapolating the present.

Conclusion: part of the demand will be real, but a significant fraction is hype.

What uses of AI justify system-scale energy priority?

If you have to prioritize, the answer is clear: health and long-term care. Diagnosis, hospital management, treatment optimization, reduction of medical errors, clinical trials. There, AI can have direct and measurable impacts on quality of life and survival.

Secondly, the optimization of the food system, especially to reduce waste. These are areas where modest improvements can generate enormous benefits in a very short time.

The rest – trivial or cosmetic applications – should not compete for scarce energy resources.

Can restarting large nuclear power plants solve the problem?

It helps, but only marginally. Even restarting several plants in the U.S., the impact would be small compared to the tens of gigawatts needed. And the problem isn’t just American: Much of the new demand will be outside the U.S., in countries without nuclear infrastructure.

Fission may be part of the mix, but not a dominant solution for AI-associated energy growth.

Why does China build nuclear power plants so fast and the West doesn’t?

Because China is an authoritarian system. Decide and execute. In democracies such as the US or Europe, there are regulators, judicial processes and local opposition (NIMBY). It is not a technical failure, it is a political and social difference.

To compare deadlines between China and the West is to ignore how democratic societies work. And Smil is clear: he doesn’t want to live in a system like China’s just to build faster.

Does the idea of data centers in space make sense?

It’s a classic example of promises with no track record of fulfillment. Failed predictions about Mars, Hyperloop or other projects are abundant. To confuse futuristic visions with real solutions is to fall back into hype.

It is not an energy roadmap. It’s narrative.

Can Europe reduce consumption without subsidies?

In practice, no. Western economies operate on generalized subsidies, direct and indirect. The clearest example is food: all food is subsidized in one way or another.

Talking about “no subsidies” is theoretically interesting, but operationally unrealistic without changing the entire economic model.

Which European energy innovations would make the most global sense?

Think on a continental scale, not a national one. For example: installing large solar plants where there is sun (Spain, Italy) and transporting electricity through high-voltage lines, as China does.

Another strategic mistake was to shut down nuclear power in countries such as Germany and then import nuclear electricity from France. Much better can be done with rational planning and real cooperation at European level.

Is European competitiveness an energy cost problem?

Not today. Global oil and gas prices are not at record highs and supply continues to rise. We are not experiencing a price crisis like the one in the seventies.

The real problem is not the cost, but the inefficient use of energy. The energy collapse has always been announced, and it has never happened. The energy has continued to flow even in the worst of times.

If you could only leave one final message, what would it be?

Use less. You can always use less.

As individuals, companies and countries, we are far from exhausting the opportunities to reduce consumption. There is no technology that compensates for a waste-based system.

The final example is telling: single-use plastic packaging in food that previously didn’t need it. Only by eliminating practices like this would millions of tons of fossil fuels be saved per year.

Efficiency doesn’t start with reactors or algorithms. It starts with everyday decisions and basic policies.

The message is uncomfortable, but simple: the solution is not to produce more energy, but to need less.

Distinguido Profesor Emérito de la Facultad de Medio Ambiente en Universidad de Manitoba