AI-generated summary

Until recently, biotechnology was confined to elite institutions due to high costs and specialized equipment requirements. However, the emergence of biohacklabs and community synthetic biology platforms is democratizing access, enabling students and entrepreneurs to experiment and innovate in more affordable, collaborative spaces. Synthetic biology is recognized as a transformative technology poised for significant growth, with market projections estimating expansion from $20 billion in 2025 to $50 billion by 2030. Initiatives like the DIYbio network and cloud labs facilitate open access to biotechnology tools, allowing remote experimentation and fostering a distributed ecosystem where cutting-edge research is no longer limited to well-funded labs.

This democratization is driving innovation by lowering barriers and encouraging “doing more with less,” exemplified by projects such as PlomBOX, a low-cost biosensor for citizen science applications. Success stories like Barcelona-based Dan*na demonstrate how open, cost-effective ecosystems can accelerate the commercialization of synthetic biology innovations. However, increased accessibility also raises ethical concerns, such as biosecurity risks associated with gene-editing technologies. Community labs address these through self-regulation and biosafety training. While distributed biotechnology won’t replace large research centers, it complements them by nurturing new ideas and talent. Integrating governance and ethics with entrepreneurship programs is crucial to ensuring responsible innovation, signaling a future where breakthroughs may emerge not only from traditional institutions but also from grassroots, community-driven efforts.

Biohacklabs and community synthetic biology platforms are democratizing a sector that was previously restricted to universities and multinationals.

Until recently, biotechnology was a domain reserved for universities, leading research centers and multinationals. Setting up a molecular biology laboratory implied millions of dollars in investments in equipment and restricted access to an elite of scientists. Today, however, this panorama is changing. Biohacklabs and community synthetic biology platforms are democratizing access to biotechnology, bringing it closer to students and entrepreneurs who find in these environments a place to experiment, learn and undertake.

The MIT Technology Review identifies synthetic biology as one of the technologies with the greatest impact of the decade. Various market reports

Community labs and open biology

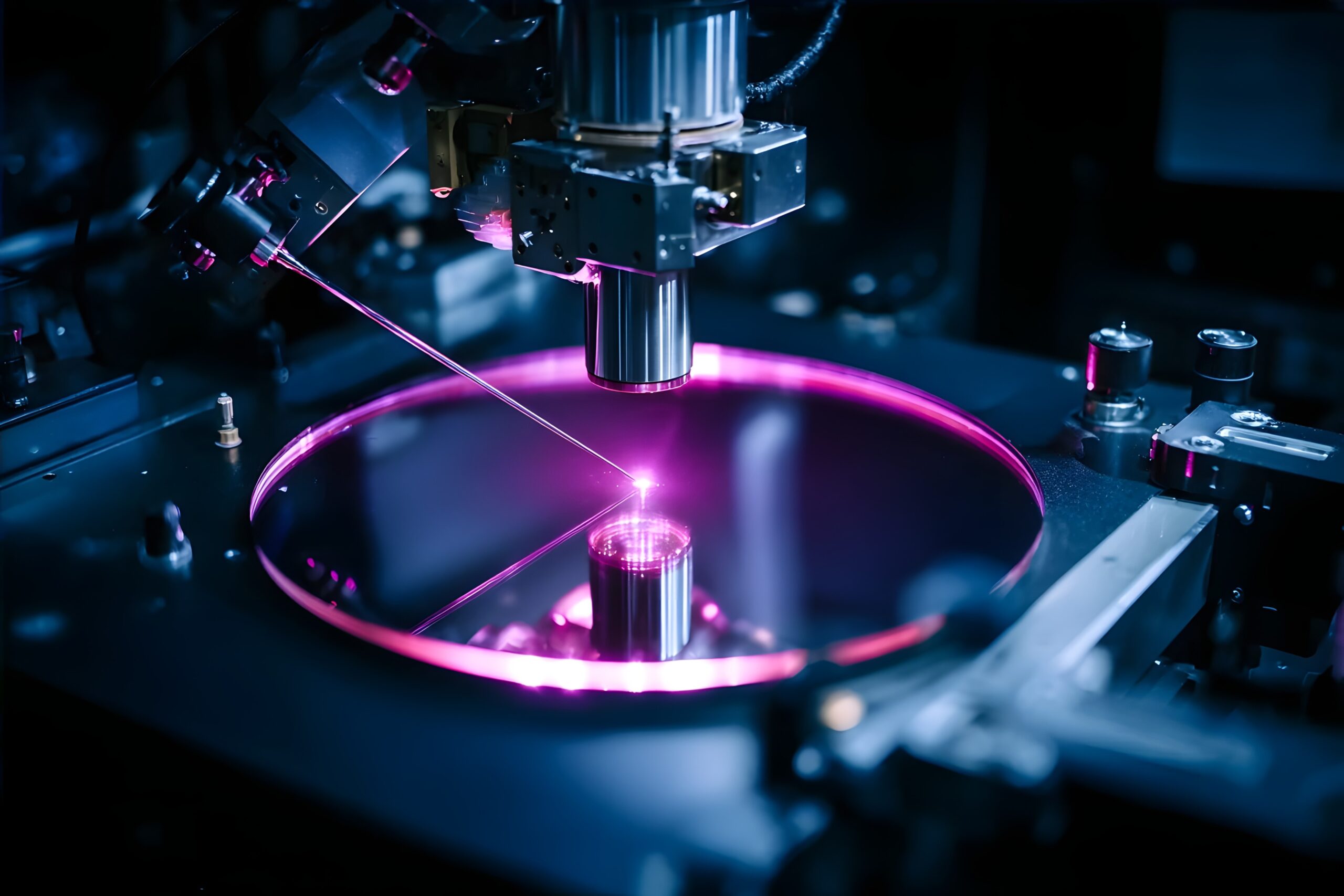

The DIYbio network, created in 2008, is one of the benchmarks of the citizen biology movement. Its objective is to give open access to biotechnology and promote safe and responsible practices in communities of amateurs and entrepreneurs. Community associations and laboratories in European and Latin American cities have made low-cost PCR equipment, gene-editing kits or microscopes available to their members.

Initiatives such as Hackteria, based in Switzerland, or collectives such as Laboratorio Vivo in Mexico show that this trend is expanding in different cultural contexts. Added to this are the so-called

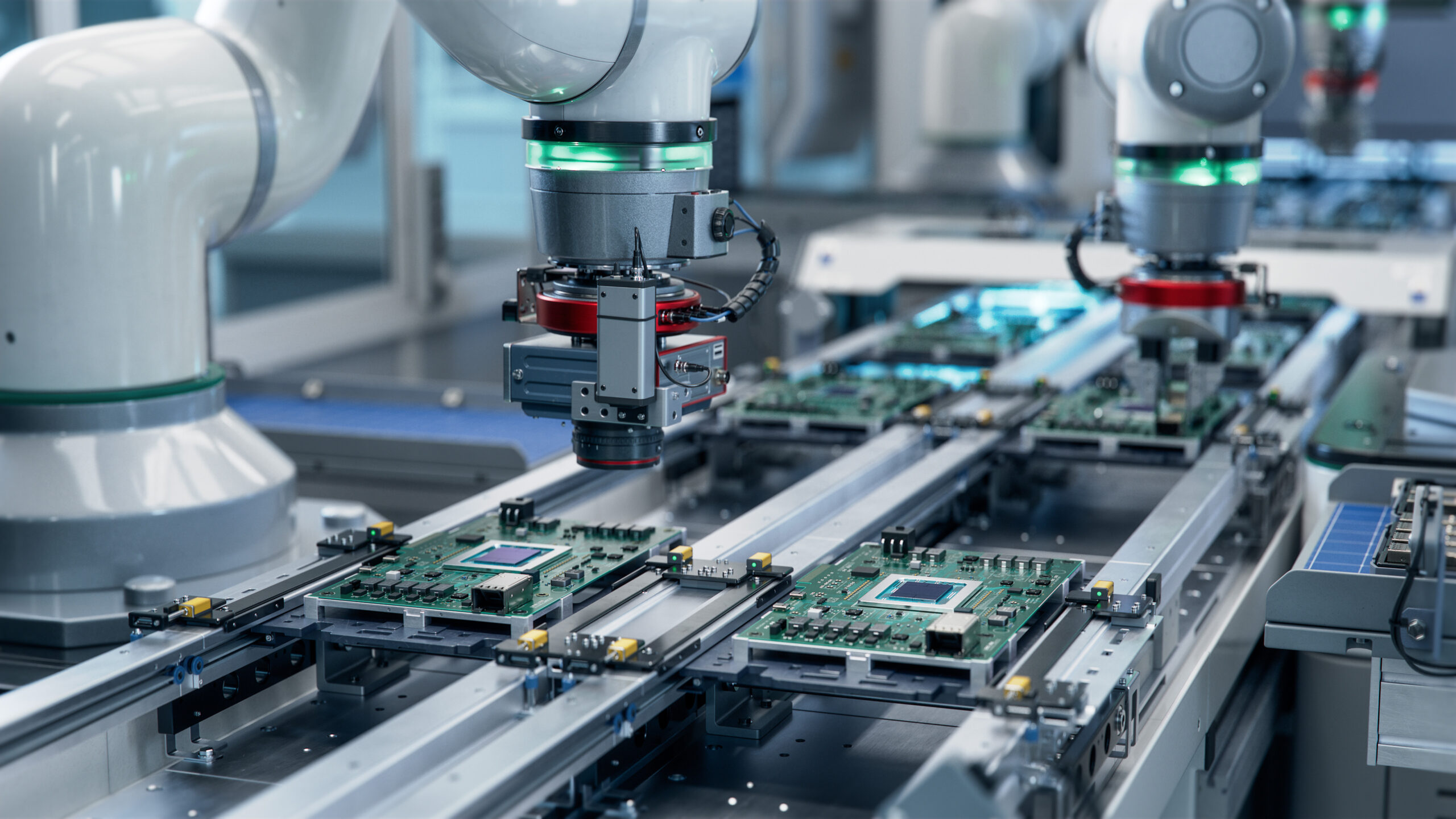

This ecosystem is supported by a real fall in access barriers. Instruments that were once prohibitive are now at classroom prices, bringing professional workflows closer to low-budget labs. And when physical space is not available, cloud labs allow you to design and execute experiments remotely with advanced instrumentation.

A consolidated example in Europe is the BioHack Academy of the Waag open laboratory (Amsterdam), which in its 2025 edition continues to train participants in the construction of equipment with open hardware and in the operation of an accessible wetlab. The program ranges from basic techniques to biomaterials projects, and over time has expanded as an international network of hands-on learning.

The logic of “doing more with less” not only reduces costs, but also orients the prototypes towards citizen use. The PlomBOX project is a good example: a low-budget lead biosensor designed to bring the detection of contaminants closer to the field of citizen science. Their proposal demonstrates that synthetic biology can be translated into accessible devices without sacrificing reliability and experimental traceability.

This path from accessibility to impact is also observed when prototypes and talent trained in open environments find market traction. In Spain, Barcelona-based Dan*na (Artificial Nature, S.L.) announced in October 2025 the leap to the industrial production of its bioplastic PLH – biobased copolyester with a world patent – after validating the scaling at the Barcelona Science Park. Although not born from a community biohacklab, the case shows how an ecosystem with decreasing costs, distributed talent and open networks accelerates the translation of biomaterials into real applications.

Ethical risks and dilemmas

The democratization of biotechnology, however, is not without risks. For example, open access to gene-editing tools such as CRISPR raises the possibility of organisms being manipulated without the necessary biosecurity measures. The UN, in a recent report , warns that synthetic biology can accelerate advances in health, energy and the environment, but requires strong governance frameworks to prevent misuse or accidents.

The same report emphasizes the need to establish biosafety and traceability protocols even in community settings. The communities themselves, in fact, are aware of this dilemma. DIYbio, for example, adopted a code of good practice that requires participants to undergo basic biosafety training before entering laboratories. It is a form of self-regulation that seeks to balance openness with responsibility.

Distributed biotechnology will not replace large research centers, but it can become a fundamental complement.

Fostering the connection between community laboratories and entrepreneurship programmes, as is the case with Inspiratech of the Bankinter Innovation Foundation, is the key to accelerating new solutions in health, sustainability or food. And at the same time, integrating governance and ethics protocols from the beginning ensures that innovation is channeled into positive impacts.

Synthetic biology is set to be one of the great technological transformations of the decade. And the leaders of this transformation may not only come from universities or multinationals, but also from garages, community spaces or startups that emerged from open collaboration. The interesting question is no longer only what innovations we will see, but who will carry them forward, under what values and with what responsibilities.