AI-generated summary

In her analysis, María Marced, former President of TSMC Europe, builds on the view that the semiconductor industry is undergoing exponential growth driven by artificial intelligence (AI), foundry consolidation, and geopolitical factors. She highlights that semiconductors have evolved from enabling technology to a major economic driver, rising to the third most profitable industry by the early 2020s, reflecting their growing role in innovation, economic value creation, and industrial investment. Technological waves, from computing to mobile devices, have shaped demand, with AI—especially edge AI integrated in devices and industrial systems—now fueling the next growth phase. Market forecasts anticipate the industry’s value doubling to around $1.3 trillion by 2030, with Europe’s key growth opportunities lying in automotive, industrial automation, and AI applications closely tied to its industrial base.

Marced emphasizes the sector’s shift from vertically integrated companies to specialized business models—foundries, fabless design firms, and providers of electronic design automation and intellectual property tools—requiring Europe to strategically build competitive positions in specific value chain segments rather than replicating full-stack models. She stresses the importance of the EU Chips Act in fostering a coordinated European semiconductor ecosystem through pan-European clusters focused on promising technologies like photonics, power semiconductors, and RISC-V architectures. The main challenge is overcoming fragmented national approaches by promoting collaboration, avoiding duplication, and implementing a unified industrial strategy. This coordinated effort is essential for Europe to effectively seize the semiconductor growth opportunity and transform its dispersed assets into global leadership.

Maria Marced analyses the European industrial strategy in semiconductors: AI, specialisation, technology clusters and the role of the EU Chips Act.

In the previous article in this series, Ajit Manocha placed the semiconductor industry in a phase of exponential growth, driven by artificial intelligence, the concentration of the foundry model and an increasingly decisive geopolitical context. The intervention of María Marced, former President of TSMC Europe, expands on this diagnosis with a complementary view: how this growth translates into real economic value, what technologies explain the next stage and what type of industrial models make the most sense for Europe.

With more than three decades of experience in the sector and a track record linked to some of the most relevant companies in the global ecosystem, Marced offers a clear and direct reading of the moment that the semiconductor is experiencing and the strategic decisions that are opening up in the coming years.

From technological impact to economic leadership

Maria Marced begins by placing the semiconductor industry on an axis that goes beyond technological innovation. Throughout this century, he explains, the sector has climbed positions steadily in the ranking of average economic profitability by industry.

In the first decade of the century, semiconductors ranked eleventh. In the second decade, they rose to fourth. And in just the first years of the current decade, they have reached third place, only behind sectors such as high tech and biotechnology. An evolution that reflects how semiconductors have gone from being an enabling industry to becoming one of the main engines of global economic growth.

This rise, Marced stresses, combines two simultaneous effects: on the one hand, the ability of the chip to drive innovation in all sectors; on the other, its direct contribution to the creation of economic value, qualified employment and industrial investment.

The big waves that explain the growth

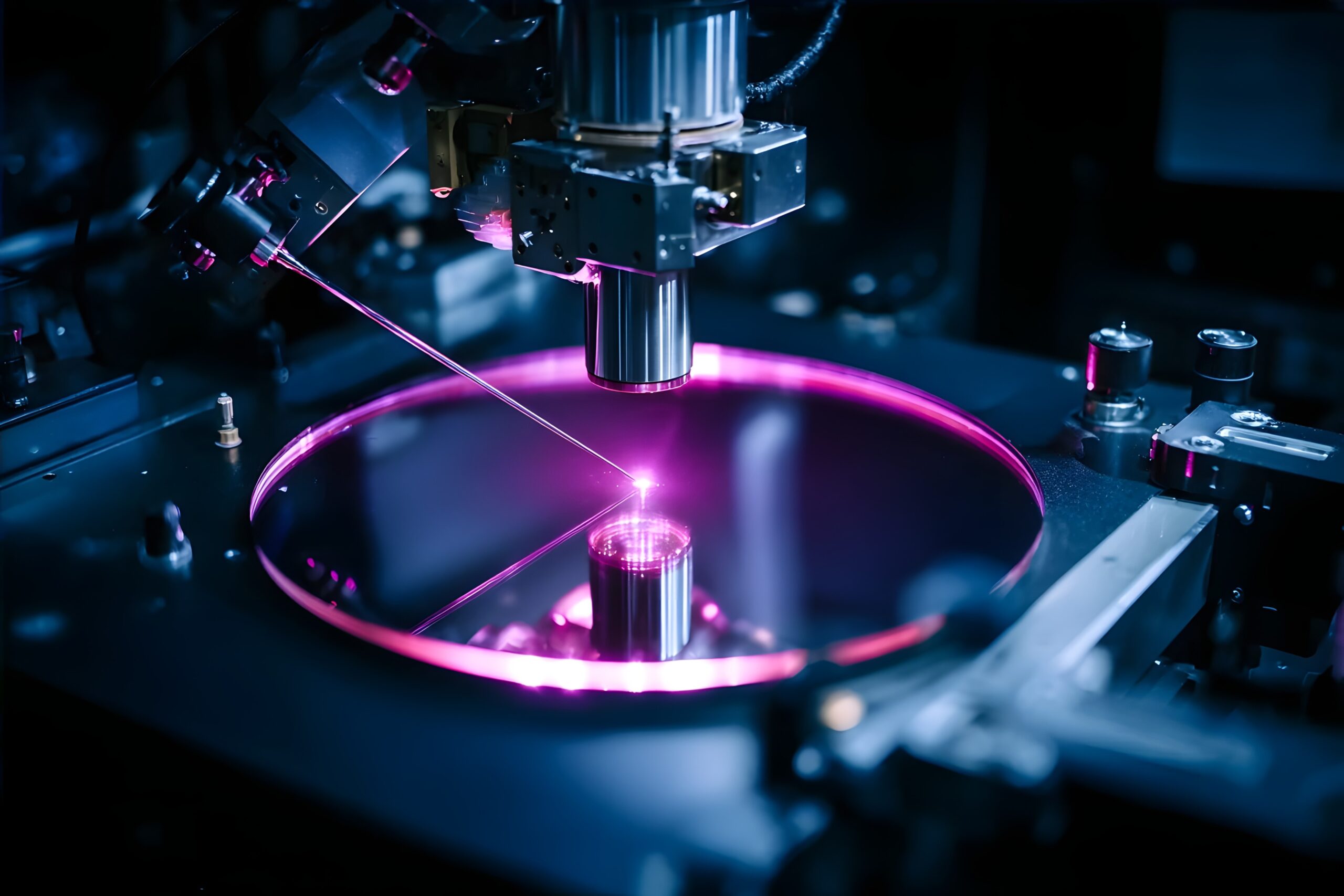

To understand this journey, Marced identifies the technological waves that have driven the demand for semiconductors in recent decades. During the early years of the 21st century, computing was the main driver. Later, the rise of the mobile phone and, especially, the smartphone, multiplied the volume and diversity of chips needed.

The next big wave is already underway: artificial intelligence. And, unlike previous stages, its impact is not limited to the cloud. Marced focuses on AI at the edge, integrated into devices, machines and industrial systems. In an environment where everything is connected, each element incorporates growing layers of intelligence, structurally expanding the demand for semiconductors.

Growth to 2030: a clear opportunity for Europe

In market terms, Marced puts the industry’s forecast at around $1.3 trillion in 2030, from a base of close to $600 billion in 2021. It acknowledges that growth has been more contained in the last two years, with a slight improvement in the current year, but maintains the expectation of expansion in the medium term intact.

This estimate aligns with the most commonly cited figures in the industry and complements the vision presented by Ajit Manocha, which expands the perimeter of analysis by incorporating the economic value of chips designed for internal use by big tech. Two different approaches converge on the same conclusion: the semiconductor industry maintains a solid structural growth trajectory for the next decade.

What is relevant, from a European perspective, is where this growth will come from. Marced highlights three main areas: automotive, industrial, and artificial intelligence applications. These segments are closely linked to the European productive fabric, where the demand for chips is associated with electrification, automation, energy efficiency and industrial digitalisation.

This growth profile connects directly with the continent’s industrial capacities and opens a window of opportunity to strengthen its position in the global value chain.

AI Beyond Hype: Increasing Hardware Complexity

One of the most interesting moments of his speech comes when addressing the debate on the efficiency of AI. Marced mentions the case of DeepSeek, a Chinese solution that generated concern in the sector by demonstrating advanced capabilities on nodes less sophisticated than those used by models such as ChatGPT.

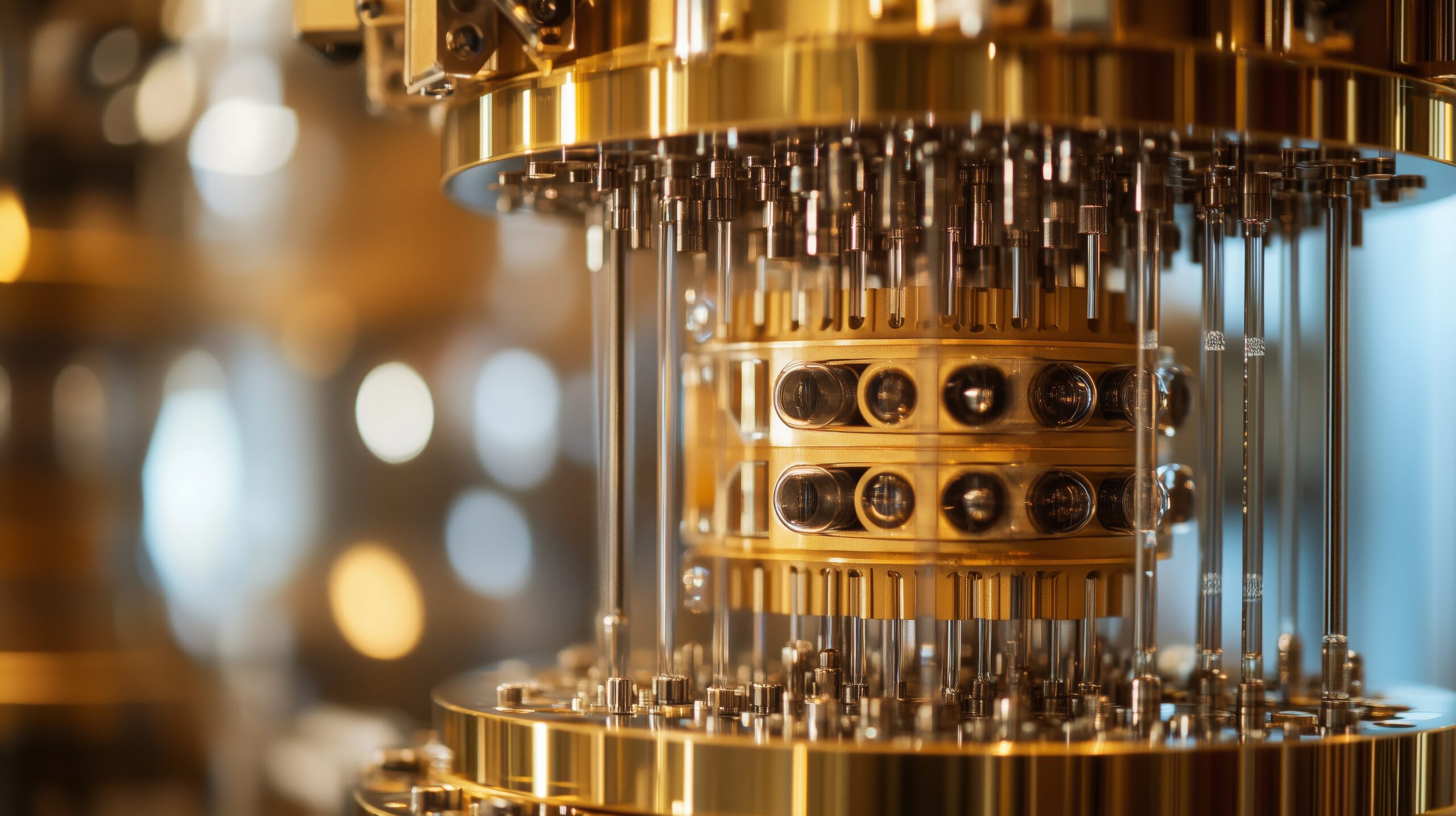

The question immediately arose: could these kinds of developments reduce the need for advanced chips? Marced’s answer is clear. Artificial intelligence is in an early phase, mainly focused on generative AI. The next stages – agent AI, closer to human interaction, and physical AI, linked to robotics and autonomous systems – will increase the complexity and demands of hardware.

Applications such as health, industry or robotics expand the spectrum of use of AI and reinforce the need for specialized, efficient and increasingly sophisticated semiconductors.

Business models: from integration to specialization

Maria Marced closes her speech with a reflection focused on the evolution of the business models of the semiconductor industry, an element that she considers decisive to understand its current structure and to guide any industrial strategy in Europe.

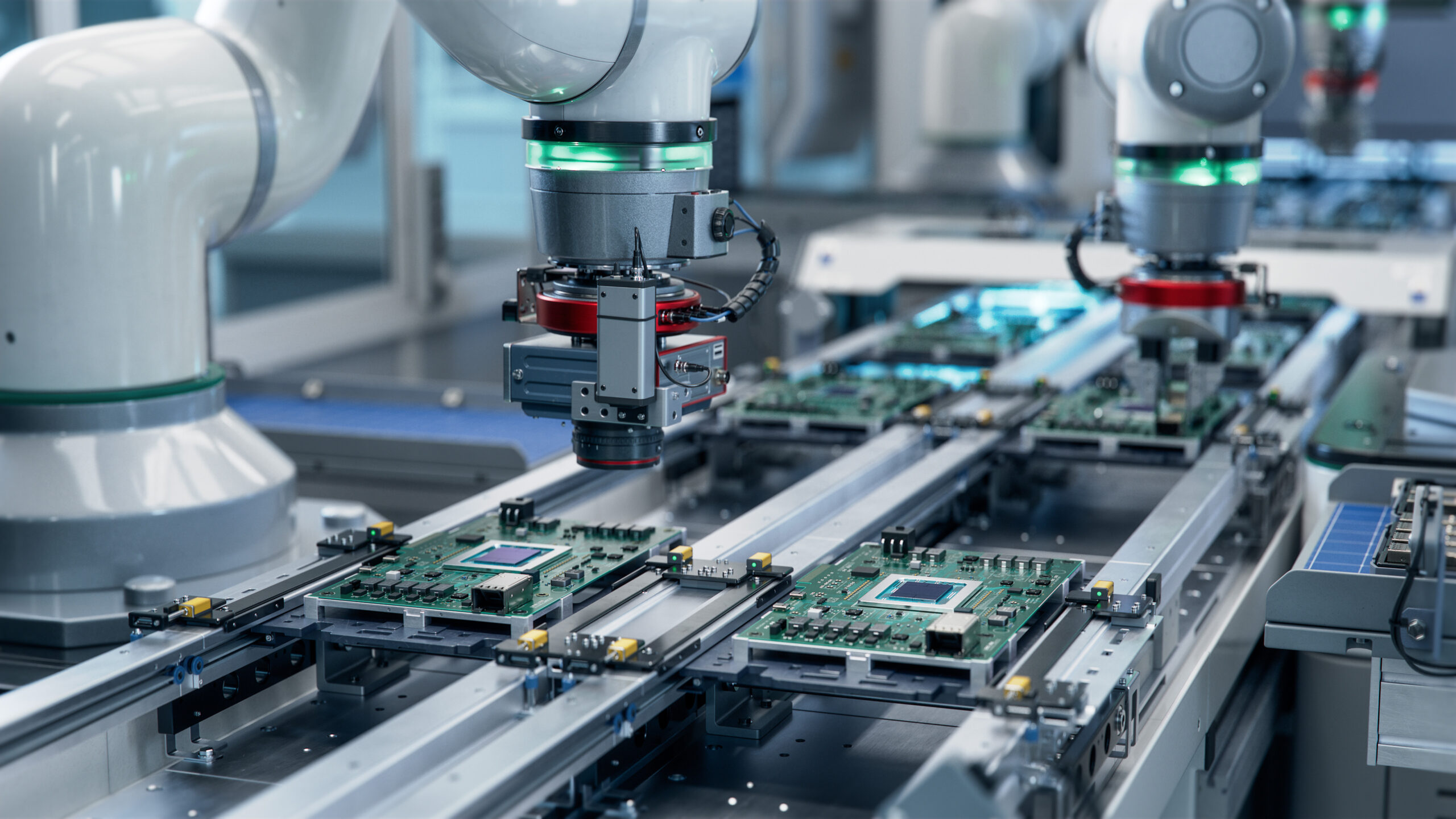

At the beginning of this century, he explains, the dominant models were IDMs (Integrated Device Manufacturers), vertically integrated companies that designed, manufactured and marketed their own chips. Companies such as Intel, Texas Instruments, NXP Semiconductors and Infineon concentrated a large part of the sector’s value in a more closed industrial context, with shorter supply chains and a significantly lower level of technological complexity than today.

Over time, the sector has become a fully global industry, and this globalization has been accompanied by a very significant increase in technological and economic complexity. Marced stresses that this process has transformed the structure of the sector, favouring a progressive specialisation of business models. Each part of the value chain has tended to concentrate on very specific functions, developing increasingly deeper and more differentiated capabilities.

The result is a much more segmented ecosystem, in which the models that are gaining weight are organized around specific functions. Marced clearly identifies four main areas: foundries, focused exclusively on manufacturing; fabless companies, specialized in design; and providers of electronic design (EDA) and intellectual property (IP) tools. This specialization, he explains, has allowed the industry to advance more quickly, improve efficiency and respond to increasingly diverse and demanding markets.

From this perspective, Marced points out that any attempt to strengthen the semiconductor industry in Europe – and in Spain – must start from this structural reality. Strategic reflection does not involve reproducing complete integrated models, but rather analysing in which specific parts of the value chain a solid and competitive position can be built. Specialization thus appears as a path aligned with the natural evolution of the sector and with the way in which value is generated today in the global semiconductor ecosystem.

EU Chips Act: coordination, clusters and European implementation

In the dialogue following the presentations, María Marced directly addresses the role of the EU Chips Act and, in particular, the challenges of its second phase, in which she actively participates as leader of the Industry Advisory Group. His diagnosis is based on a clear idea: Europe has many of the necessary ingredients to strengthen its semiconductor industry, but the main challenge is in how they are organised and coordinated.

Marced stresses that the continent has top-notch research centers, a solid educational system, technical talent and companies with relevant capabilities in different segments of the value chain. However, these strengths are fragmented across countries and regions, limiting their impact. In his opinion, the risk does not lie in technology or future demand, but in the lack of a truly European strategy, beyond the sum of national plans.

In this context, Marced insists on the need to move towards a logic of pan-European clusters, aligned with the priorities of the Chips Act. He mentions specific areas where Europe has a clear opportunity if it acts in a coordinated manner: photonics, advanced power semiconductors and wide band gap, RISC-V and certain areas of packaging. Emerging technologies in which, he explains, there is still no clearly defined global leadership and where Europe can build a relevant position.

For these clusters to work, Marced points out a precise distribution of roles. The role of public administrations must focus on facilitating: financing, land, talent and infrastructures. Technical governance, on the other hand, must fall to the actors of the ecosystem themselves. The key is to avoid duplication of efforts and to encourage collaboration between regions that today compete with each other in similar areas.

His message is especially clear when he addresses the scale of the challenge: as long as Europe continues to function as the sum of 27 national strategies, the impact will be limited. The ambition of the EU Chips Act is to move towards a joint execution, capable of transforming dispersed capacities into a true European semiconductor industrial ecosystem.

A decisive moment for Europe

María Marced’s speech leaves a clear idea: Europe is facing a window of opportunity to strengthen its position in the global semiconductor industry. The technological context, the growth in demand and the evolution of business models all play in their favour. The difference will be made by the ability to execute a common strategy.

In this scenario, the EU Chips Act is emerging as a key lever to transform dispersed capacities into a coherent industrial ecosystem. According to Marced, the challenge is not to identify promising technologies or to mobilise talent, but to coordinate efforts, avoid duplication and move towards a logic of European clusters aligned with clear priorities.

Europe has relevant assets in areas such as automotive, industry, photonics, advanced power or the design of emerging architectures. Turning this potential into leadership requires moving from the sum of national initiatives to a truly European implementation, where collaboration between regions, companies and research centres is structural.

The final message is straightforward: semiconductor growth is underway and will continue for years to come. The EU Chips Act provides the framework for Europe to capture a significant share of that growth. The key now lies in how it is implemented and in the ability to move in a coordinated manner towards a more integrated and competitive industrial ecosystem.

Maria Marced’s analysis connects directly with the vision presented by Ajit Manocha in the previous article[a1]: a semiconductor industry in full structural expansion, driven by artificial intelligence and by a demand that will continue to grow in the next decade. If Manocha underlined the magnitude of the moment and the strategic relevance of the sector on a global scale, Marced now focuses on how Europe can translate this growth into its own industrial capacity. In this context, the EU Chips Act appears as the tool to move from diagnosis to action, aligning specialization, clusters and joint execution. The opportunity is defined; The next step is to translate that framework into concrete results within the European semiconductor ecosystem.

See the full presentation

To learn more about Maria Marced’s analysis, you can watch her full presentation at the Future Trends Forum:

Maria Marced: “The Chip Industry Is Transforming. Europe Still Has Time” #Semiconductors

In the next article in this series, we will continue to explore the keys to the future of semiconductors from new perspectives from the experts of the Future Trends Forum.

Expresidente de TSMC Europa