AI-generated summary

Fusion energy has long been viewed as a potential solution to the global energy crisis, promising vast electricity generation without CO₂ emissions or long-lived radioactive waste, and fueled by abundant, widely available materials. However, transitioning from theory to practical application remains challenging. The Future Trends Forum (FTF) recently hosted a webinar featuring Pablo Rodríguez-Fernández from MIT’s Plasma Science and Fusion Center, who discussed the current state and roadmap for fusion technology. The FTF report, developed with insights from 30 international experts, highlighted five priority areas to accelerate fusion development: advancing experimental reactors, fostering public-private partnerships, addressing talent shortages, updating regulatory frameworks, and improving public communication.

Rodríguez-Fernández emphasized fusion’s advantages over fossil fuels and renewables, such as zero greenhouse gas emissions, intrinsic safety, and scalability. Magnetic confinement using tokamak reactors, enhanced by high-temperature superconductors, is the leading approach to achieving net energy gain. Yet, significant engineering challenges remain, including heat extraction, radiation-resistant materials, tritium fuel cycling, plasma stability, cost reduction, and system integration. Despite these hurdles, the fusion sector has attracted over $8 billion in private investments, driving progress alongside major public initiatives like ITER and IFMIF-DONES. Fusion’s potential to deliver stable, clean, and abundant energy positions it as a promising contributor to the future energy mix, complementing renewables and aiding global decarbonization efforts.

What barriers are holding back the development of nuclear fusion? What role do artificial intelligence, deeptech startups and public-private collaboration play in this energy race? Pablo Rodríguez-Fernández (MIT) responds in a new webinar at the Future Trends Forum

Fusion energy has been considered a possible structural solution to the global energy problem for decades. In theory, it makes it possible to generate large amounts of electricity without CO₂ emissions, without long-lived radioactive waste and with virtually unlimited fuel. But the distance between theory and actual implementation has been, so far, abysmal.

Within the framework of the Future Trends Forum (FTF), the think tank of the Bankinter Innovation Foundation, a webinar was held with Pablo Rodríguez-Fernández, principal investigator at the MIT Plasma Science and Fusion Center, who specialises in modelling and simulation of magnetic confinement reactors. The session was conducted by Marce Cancho, director of the FTF, and had a double objective:

- To present the main conclusions of the report Fusion Energy: an energy revolution in progress, prepared by the FTF after a working session with 30 international experts.

- To delve, with the help of an active researcher, into the current state of technology and the steps necessary to make its industrial scaling viable.

This article collects the keys to the session: from the technological and climate motivation that drives fusion to the technologies that are advancing it today.

If you want to watch the full webinar, you can do so in this video:

Fusion Energy with Pablo Rodríguez (MIT)

Conclusions of the Future Trends Forum on fusion energy

Before Pablo Rodríguez-Fernández’s speech, Marce Cancho presents the main conclusions of the report prepared by the Future Trends Forum after bringing together 30 international experts in June 2025. The group identified five priority axes to accelerate the development of fusion energy:

- Technology

There is a need to move from laboratory experiments to complete fusion devices that address the challenges of system integration and operation. The construction of these experimental reactors is key to maturing the technology and reducing technical uncertainties.

- Public-private collaboration

The mobilisation of capital on a large scale and the creation of strategic alliances between administrations and companies are essential. Over the past five years, private investment in fusion startups has increased significantly, with prominent players in both the United States (such as Commonwealth Fusion Systems) and Europe (such as Proxima Fusion, Renaissance Fusion , or Tokamak Energy).

- Talent

There is a critical shortage of professionals with specialized knowledge in plasma physics, cryogenics, superconductivity, and other related fields. Training and retaining qualified talent is an essential requirement for fusion projects to be developed on an industrial scale.

- Regulation

Although fusion presents very different risks than nuclear fission, many regulatory frameworks still apply legacy criteria. The report points out the need to design specific regulatory environments that accompany technological progress, without generating unnecessary bottlenecks.

- Communication

It is necessary to build a clear, realistic and understandable narrative about nuclear fusion. Public acceptance will be a determining factor for its implementation, and it will only be achieved through rigorous, evidence-based communication.

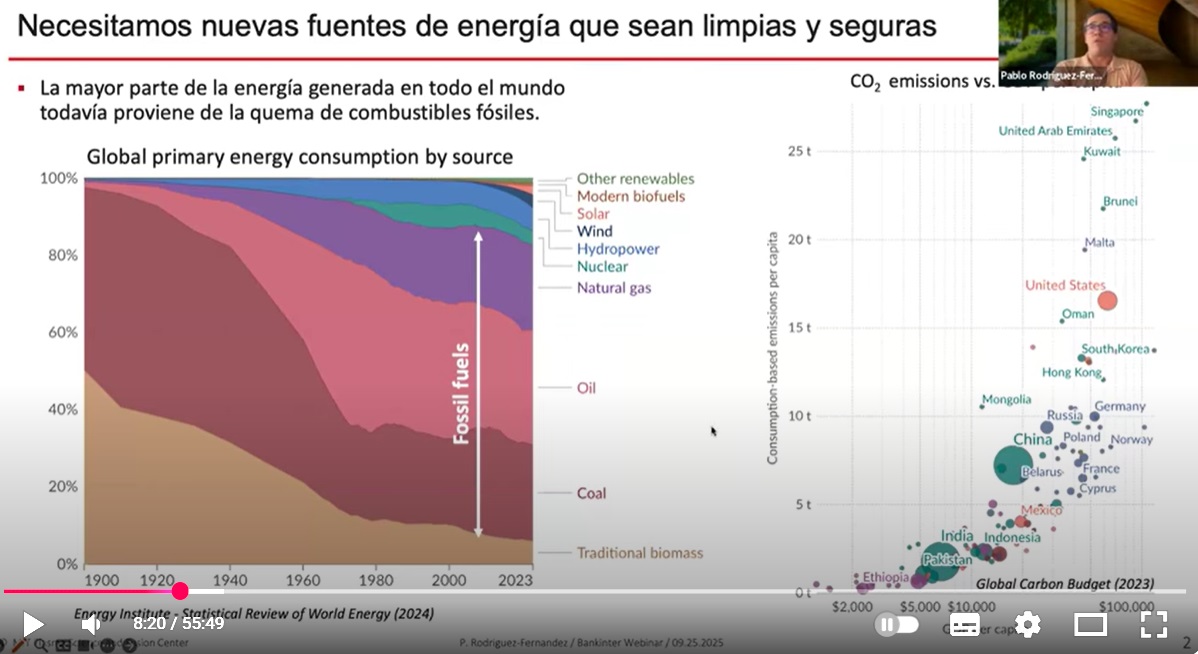

Why we need new sources of energy

Pablo Rodríguez-Fernández opens his speech by recalling the reason why research into nuclear fusion is relevant today. More than 80% of the world’s primary energy is still dependent on fossil fuels. This situation generates a high volume of CO₂ emissions, directly correlated with economic development and increased energy consumption.

Even with sustained growth in renewables, projections indicate that by 2050 a significant share of electricity supply – more than 50% in countries such as the United States – would still come from fossil sources. At the same time, global energy demand will continue to increase, driven by population growth and the industrialization of emerging economies.

Source: webinar

The energy transition therefore requires new technologies capable of covering the demand for base energy, without depending on weather conditions or requiring mass storage. These technologies must simultaneously meet five requirements:

- Not to emit greenhouse gases.

- Use plenty of fuel.

- Have a high safety profile.

- Be scalable in time and space.

- Integrate into existing power grids.

In this context, nuclear fusion is proposed as a real alternative in the medium term, capable of complementing renewables and contributing to the decarbonisation of the energy system.

What is nuclear fusion and how does it work?

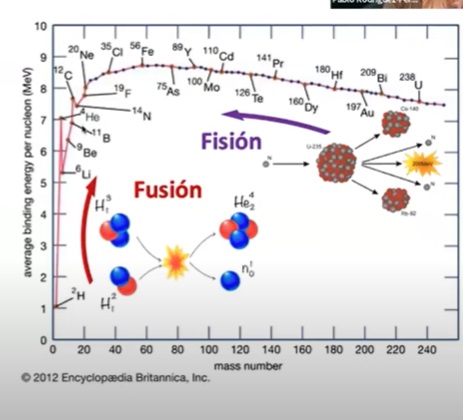

Nuclear fusion consists of reproducing on Earth the same physical process that occurs inside the Sun: joining light atomic nuclei – usually isotopes of hydrogen, such as deuterium and tritium – to form a heavier nucleus, releasing a large amount of energy in the process.

For this reaction to occur, it is necessary to heat the fuel to more than 100 million degrees, which generates a state of matter called plasma, which is extremely hot and difficult to contain.

The main challenge is not to provoke the reaction, but to confine that plasma without it touching the walls of the reactor that would melt instantly).

To solve it, a device called a tokamak is used, which creates a doughnut-shaped magnetic field capable of keeping the plasma floating, as if it were “levitating” inside the reactor.

Unlike nuclear fission, which splits heavy atoms and generates long-lived radioactive waste, fusion does not produce polluting emissions or hazardous waste in the long term. In addition, the base fuel (deuterium and lithium to generate tritium) is abundant and distributed in a geopolitically stable way.

Source: webinar

The main challenge is not in the physical principle, but in the engineering needed to contain and keep the plasma – an extremely hot and conductive substance – in stable conditions for long enough for the reaction to generate more energy than it consumes.

To achieve this, there are several technological approaches. The one that concentrates the most attention and resources is magnetic confinement using tokamak devices, where high-field magnetic fields in a toroidal shape control the plasma. Inertial confinement and other alternative approaches are also being investigated.

One such alternative, laser inertial confinement, achieved an unprecedented milestone in 2022: obtaining a net energy gain in a fusion reaction. The experiment, carried out at the National Ignition Facility (NIF), showed that it is possible to release more energy than is invested in heating the plasma, although it is still a long way from a commercial solution. Pablo Rodríguez mentions it as an important advance, but recalls that this approach is different from the one he is researching at MIT – magnetic confinement fusion – and that each technological path has its own challenges. This type of progress will be the subject of analysis in future seminars of the Future Trends Forum.

Technologies to achieve fusion

As we have just mentioned, the most advanced approach to achieving controlled nuclear fusion is magnetic confinement of plasma, using devices called tokamaks. In them, very strong magnetic fields are used to keep the plasma – a mixture of nuclei and electrons at very high temperatures – isolated from contact with the walls of the reactor.

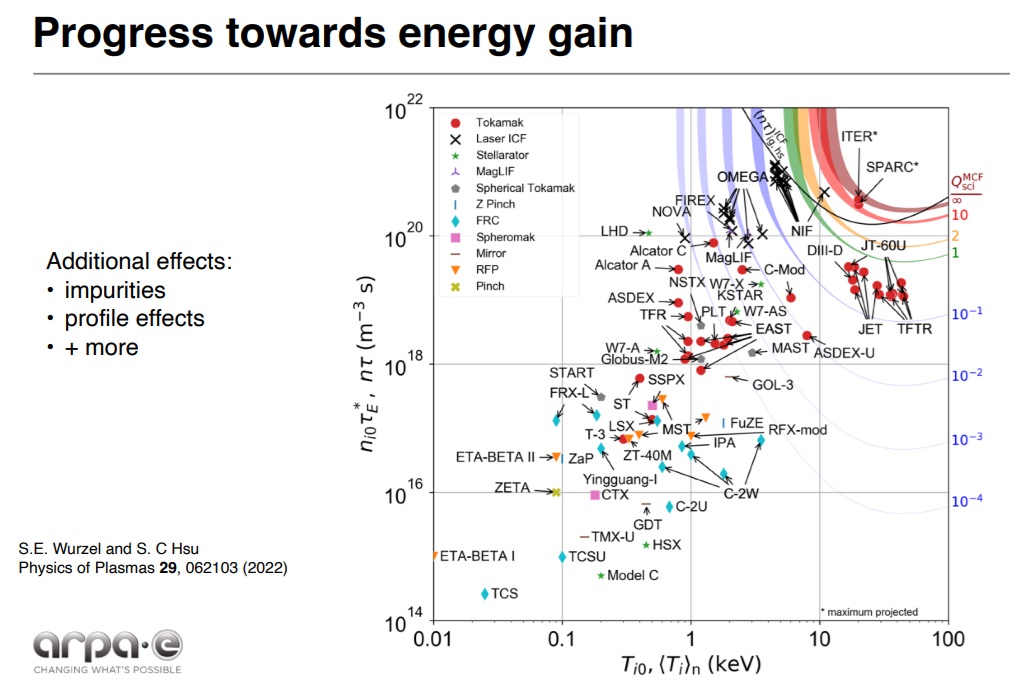

A key concept for assessing whether a reactor is achieving its goal is the gain factor Q. This value measures how much energy the plasma generates compared to the energy injected into it to maintain it. If Q < 1, the system loses energy. If Q = 1, the same energy is produced as is consumed. The goal for an experimental reactor like SPARC is to achieve a Q greater than or equal to 10, i.e., for the plasma to generate ten times more energy than it receives.

Source: webinar

But, as Rodríguez-Fernández points out, achieving a high Q does not in itself guarantee that a fusion plant is viable. Many other energy-consuming systems still need to be powered: cryogenics, electromagnets, refrigeration, thermal extraction. For this reason, work is also being done to optimize the complete design of the reactor, not just the efficiency of the plasma.

This is where high-temperature superconductors (HTS) come into play. These materials make it possible to generate much stronger magnetic fields than traditional superconductors, making it possible to build more compact, efficient and potentially cheaper reactors. This is the basis of the design of SPARC, the experimental reactor developed by Commonwealth Fusion Systems together with MIT.

Rodríguez-Fernández participates in this project from the area of predictive modeling, using advanced simulations to anticipate the behavior of plasma under different operating conditions. This approach reduces technical uncertainties and accelerates the development of reactors with a sound scientific basis.

Key projects in the fusion race

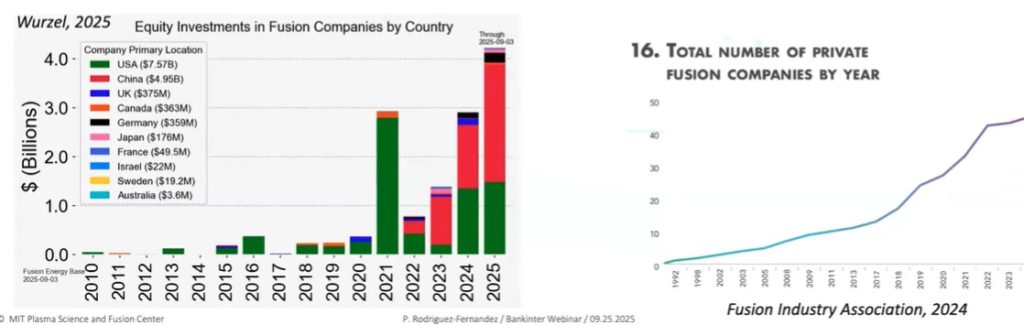

During the webinar, Pablo Rodríguez insists that recent advances in materials – especially high-temperature superconductors (HTS) – have been a turning point for fusion energy. These materials make it possible to build more compact and efficient reactors, capable of generating much stronger magnetic fields. This technological leap has been key to attracting large-scale private investment and accelerating the pace of development.

In the last five to six years, investment in fusion startups has skyrocketed. Currently, there are more than 8,000 million dollars invested in the private sector globally, with more than 40 different devices in development. At least seven companies exceed $200 million in venture capital. In 2025 alone, the combined investment between China and the United States is estimated to exceed 4,000 million dollars.

The most representative case is Commonwealth Fusion Systems, an MIT spin-off that is leading the development of the SPARC reactor, with private funding that already exceeds 3,000 million dollars. The project combines plasma physics, advanced simulation and HTS technology, and seeks to demonstrate that it is possible to achieve net-energy plasmas before 2030.

In Europe, startups such as:

- Next Fusion (Germany)

- Renaissance Fusion (France)

- Tokamak Energy (UK)

All of them, represented in the forum. Also noteworthy are TypeOne Energy (USA) and OpenStar (New Zealand). Each explores different approaches – from spherical tokamaks to stellarators – with the common goal of accelerating the development of commercial reactors.

Source: webinar

This private ecosystem does not replace large public programs, but it does complement them. In parallel, projects such as:

- ITER: an international consortium that seeks to demonstrate the scientific feasibility of large-scale fusion.

- IFMIF-DONES: focused on the validation of materials in the face of extreme conditions.

- SMART: a Spanish project in which Rodríguez-Fernández’s group is contributing with advanced simulations.

The combination of private investment, scientific leadership and international cooperation is marking a change of stage. Fundamental research has given way to an applied engineering phase, with tighter timelines and grid-oriented targets.

Technological challenges to be solved

According to Pablo Rodríguez-Fernández, making fusion a practical and competitive source of energy does not depend solely on achieving a good energy gain factor. There are other fundamental technical challenges that are still unsolvable and that must be addressed before a functional fusion plant can be built.

1. Heat extraction

Fusion plasmas release a very high amount of energy. That energy must be extracted in a controlled manner to heat water, drive a turbine, and generate electricity. The problem is that, in the process, the materials in the reactor walls can be damaged. How to design thermal extraction systems that manage these heat flows without degrading infrastructure has not yet been resolved.

2. Radiation-resistant materials

In addition to heat, fusion reactions generate high-energy neutrons. These neutrons are useful because they allow materials to be heated to extract energy, but they also pose a threat: they damage superconductors, electromagnets and reactor walls. There are no materials today that can withstand this environment for a long time. The possibility of designing reactors with interchangeable parts is being explored, but the goal is to maximize their service life to keep the plant within viable economic limits.

3. Tritium production and recycling

The main fuel for fusion is the reaction between deuterium and tritium. Deuterium is abundant, but tritium does not exist in nature in useful amounts. Fusion plants must have an internal system to generate it, through a closed cycle: the neutrons generated in fusion react with lithium and produce new tritium, which is reused in the same facility. This cycle is essential, but it has not yet been experimentally demonstrated or known if it can achieve the efficiency necessary to sustain the continuous operation of the reactor.

4. Plasma stability

It is necessary to ensure that the plasma remains stable and confined throughout the process. So-called disruptions – sudden losses of stability – and instabilities at the edge of the plasma can damage the reactor and stop the reaction. Although AI-based prediction and control systems are being developed, their effectiveness at the full reactor scale has not yet been proven.

5. Construction Cost

A melting plant must be economically viable. If construction costs are in the range of several billion euros per reactor, it will be difficult for it to compete with other energy sources. That’s why one of the current focuses of development is finding ways to drastically reduce construction and operating costs.

6. Integration of the complete system

Finally, one of the most complex challenges is the technical integration of all the subsystems in the same installation. In a fusion plant, areas with cryogenic temperatures of -250 °C (superconductors) coexist a few meters from a plasma at 100 million degrees. In addition, the turbine, cooling, fuel, magnetic fields and energy extraction systems are added. Getting all this to work in a coordinated and stable way is an engineering challenge that has yet to be demonstrated.

Why bet on the merger?

At the end of his speech, Pablo Rodríguez-Fernández reviews the characteristics that a new energy source must have to cover the space that fossil fuels must leave. Nuclear fusion, he notes, meets many of these and may be a real candidate for producing clean, abundant and scalable energy.

1. No polluting emissions

Fusion does not emit carbon dioxide or greenhouse gases. The main product of the reaction is helium, a noble, inert and non-polluting gas, which can even have industrial uses. This feature makes it an option aligned with decarbonization goals.

2. Abundant and energy-dense fuel

The necessary fuel is easily accessible:

- Deuterium is found in seawater.

- Tritium can be generated from lithium, which is present in the Earth’s crust.

Thanks to the high energy density of fusion, the necessary quantities of these materials are very small. Energy can be produced on a large scale with minimal volumes of fuel.

3. Intrinsic safety

Fusion cannot cause chain reaction accidents. If the process is interrupted, the reaction stops automatically. This makes it a safe source of energy for both people and the environment.

4. Much Less Radioactive Waste

Although fusion does not generate long-lived waste like fission, neutrons are produced that activate the structural materials of the reactor. This generates some radioactivity, but at levels much lower than those of nuclear fission. In addition, no waste is produced continuously, and treatment is limited to the disassembly of components at the end of their useful life.

5. Programmable and base power

Unlike renewables, fusion does not depend on climatic factors. It has the potential to produce constant and programmable energy, which makes it suitable to cover the base demand of the electricity system.

6. Scalable and compatible with current infrastructures

The fusion can be integrated into the existing electrical system. It uses conventional technologies such as turbines and generators, and is scalable, with plants that could range from several hundred megawatts to gigawatts of power, in line with current power plants.

Questions from the audience: radiation, Spain, AI and scientific vocation

The session closes with a round of questions from the audience, where Pablo Rodríguez-Fernández answers key questions about the impacts, applications and future of nuclear fusion.

What kind of radiation do fusion reactors generate?

Rodríguez-Fernández explains that the fusion reaction between deuterium and tritium generates neutrons, which carry most of the energy. These neutrons are captured to convert their kinetic energy into thermal energy, used to drive turbines. However, some of those neutrons interact with the reactor walls and structural systems, causing those materials to become radioactive. This radioactivity is not released into the environment, but it does require that, at the end of the plant’s useful life, the components be treated with adequate nuclear infrastructure.

In addition, he clarifies that tritium, although radioactive, has a short half-life (about 12 years) and is kept contained within the plant in a closed system. It is not released into the environment, and its management is carried out in a controlled manner.

What role does Spain play in fusion research?

Spain has had an active participation in the ITER programme and has a long history in fusion research through universities and centres such as CIEMAT. Currently, the IFMIF-DONES project, based in Granada, stands out, which will focus on studying radiation-resistant materials for future reactors. Rodríguez-Fernández points out that this type of infrastructure is essential to solve one of the key technical challenges of the merger.

In addition, he anticipates that Ángel Ibarra, head of the IFMIF-DONES project, will participate in an upcoming webinar of the Future Trends Forum together with Carlos Hidalgo, Director of the National Fusion Laboratory of CIEMAT.

How is artificial intelligence being applied in fusion?

Rodríguez-Fernández works directly in this area. He explains that AI is mainly applied on three fronts:

- Acceleration of simulations: Physical simulations of plasma are very complex and computationally expensive. AI makes it possible to build surrogate models that replace or accelerate these simulations.

- Experimental data analysis: Experiments accumulate huge volumes of data. AI is used to find patterns and extract useful knowledge from these databases.

- Control and prediction: AI is also used to anticipate plasma instabilities and design more robust control systems, although this application is still under development.

What motivated you to dedicate yourself to fusion?

With a background in industrial engineering, Rodríguez-Fernández explains that the merger attracted him because of its transformative potential. He considers it an energy that does not depend on limited resources, but on human knowledge. Developing the ability to control the very energy that makes the sun shine, he says, is one of the most inspiring challenges of our time.

What does your current job consist of?

His research group does not work directly on superconductors, but on the behavior of plasma. Its objective is to find more efficient and stable operating regimes for reactors, and to design simulations that help maximize the performance of the experiments and extract as much information as possible from them to optimize future fusion plants.

Next webinar: investment and leadership in fusion

We invite you to the next webinar of the Future Trends Forum’s fusion energy cycle, which will take place on October 16, with the participation of Sehila González. In this session we will talk about investment, the role of startups, technological challenges and why the last four or five years have been key to the private boost of the sector at a global level.

This meeting will also serve as a prelude to the webinar on October 30, in which we will have two international references:

- Susana Reyes, from the USA, Vice President of Chamber and Plant Design at Xcimer Energy, specialized in laser fusion.

- Itxaso Ariza, from the United Kingdom, Chief Technology Officer (CTO) at Tokamak Energy, one of the most advanced startups in magnetic fusion.

Two Spanish women leading the energy future from the international arena.

We look forward to seeing you all on October 16 to continue exploring, with the protagonists, how the energy of the future is built.

In the meantime, we invite you to read the report Fusion Energy: An Energy Revolution in the Making.

Investigador científico principal y jefe de grupo en el Centro de Ciencia y Fusión del Plasma del MIT