AI-generated summary

Water management in urban areas faces unprecedented challenges due to climate change, resource scarcity, and rapid urbanization, prompting a critical need to rethink traditional supply and sanitation systems. David Sedlak, a leading expert in environmental engineering and author of the “fourth water revolution,” highlights key strategies in a webinar organized by the Bankinter Innovation Foundation. These strategies include improving water use efficiency, developing non-conventional water sources like desalination and wastewater reuse, and redesigning urban infrastructure to enhance resilience against climate extremes. Sedlak emphasizes that a multifaceted approach combining technological innovation, smart policies, and infrastructure adaptation is vital for sustainable urban water management.

Efficient water use, such as reducing agricultural consumption through drip irrigation and detecting urban leaks with advanced sensors, can significantly lower demand before investing in costly new infrastructure. Non-conventional sources, including inland desalination and treated wastewater reuse, are gaining traction, with promising advances in brine valorization and decentralized water harvesting at the building level. Additionally, integrating nature-based solutions like aquifer recharge and sustainable urban drainage systems can mitigate droughts and floods by enhancing water storage and infiltration in cities. Sedlak underscores that the future of urban water relies on combining traditional infrastructure with green technologies, supported by public acceptance and transparent governance, to create resilient, sustainable water systems for the 21st century.

David Sedlak, a global expert on water resources, discusses innovative solutions to address water scarcity in cities: reuse, desalination, green infrastructure and more

Water management in cities is at an inflection point. The climate crisis, resource scarcity and urban growth challenge traditional models of supply and sanitation. In this context, the Bankinter Innovation Foundation, in its effort to disseminate the knowledge generated in the Future Trends Forum Water: our vital resource in check, has organized the webinar Water Revolution: Urban Management in the Face of Climate Change with David Sedlak, a world leader in water management and author of the concept of the fourth water revolution.

A professor of environmental engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, Sedlak addresses the strategies and technologies that are redefining water resilience in urban environments. From advanced reuse to green infrastructure to public-private collaboration, Sedlak offers a comprehensive view of how cities can adapt and ensure water security in an uncertain future.

In addition to his academic work, Sedlak is the author of key books in the water sector, such as Water 4.0 and Water for All, where he analyzes the evolution of urban water systems and proposes innovative solutions for the future.

An essential session to understand how innovation can transform water management in cities and ensure their sustainability in the 21st century. If you want to watch the webinar, you can do so here:

Webinar Water Revolution: Urban Management in the Face of Climate Change

During the webinar, David Sedlak highlights that there is no single solution to address the water crisis. The combination of technological approaches, efficient management policies and infrastructure adaptation will be key to ensuring water sustainability in the cities of the future. Throughout his speech, he addresses three major strategies: the efficient use of water, the development of non-conventional water resources and the transformation of urban infrastructures. These approaches, far from being exclusive, must be integrated to build resilient systems capable of coping with both scarcity and extreme weather events.

Efficient use of water before new investments

Before resorting to advanced and expensive technologies, efficiency in the use of water must be the first line of action. Sedlak stresses that, in many cases, improving existing infrastructure and optimising consumption can generate very significant savings without the need for large investments.

One of the clearest examples is the use of water in agriculture, which accounts for approximately 70% of freshwater consumption globally. Drip irrigation systems and precision sprinkler nozzles can reduce water consumption by 20-30% compared to traditional sprinkler irrigation systems. These types of solutions allow for more efficient use of water without compromising agricultural productivity.

In the urban environment, leak detection technologies also play a key role. In cities with old distribution networks, up to 30% of drinking water is lost due to leaking pipes. The implementation of advanced sensors and real-time monitoring systems could reduce these losses drastically, improving supply efficiency.

Sedlak insists that, before allocating large resources to new infrastructures or technologies, it is essential to evaluate water management policies. Regulatory changes that encourage efficient use and reuse can be as effective or more effective than a massive investment in new treatment or desalination plants. The combination of smart management and accessible technologies will relieve pressure on existing water resources and reduce the risk of scarcity in the future.

Non-conventional water resources

Climate change and urban growth are increasing pressure on traditional water systems. Faced with this challenge, Sedlak highlights the importance of resorting to non-conventional water sources such as desalination, drinking water reuse and brackish groundwater harvesting. These technologies make it possible to increase the availability of water beyond natural water resources, ensuring a more resilient and sustainable supply.

Desalination: Beyond the Coast

Desalination is one of the most widespread technologies for generating drinking water in areas with water scarcity. Currently, desalination plants supply millions of people in regions such as Spain, Australia and the Middle East, where freshwater sources are limited.

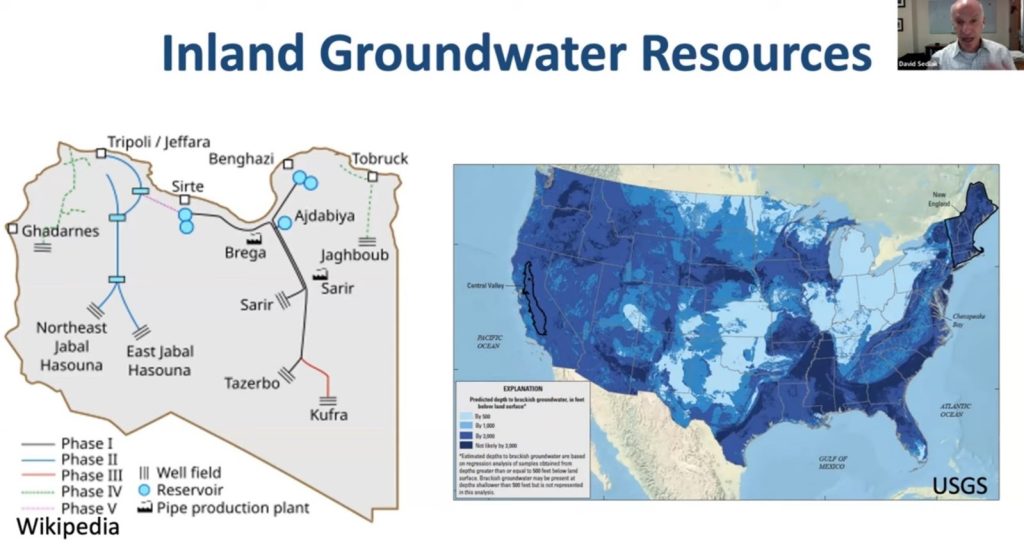

Sedlak explains that desalination by reverse osmosis has improved significantly in the last 50 years, reducing its energy consumption and increasing its efficiency. However, it points out that more than 90% of desalination plants are located in coastal areas, which limits their application to communities located far from the sea. The challenge now is to expand its use to inland regions using brackish groundwater desalination technologies.

An emblematic case is the Libyan Man-Made River Project, one of the largest hydraulic works in the world, which supplies 6.5 million cubic meters of water per day by extracting it from a fossil aquifer in the desert and transporting it to coastal cities. Despite the fact that this resource is not renewable, it demonstrates how deep groundwater can become a viable source if appropriate treatment technologies are developed.

Source: webinar with David Sedlak

In the United States, the CV Salts program in California proposed an ambitious groundwater desalination plan with an investment of 11,000 million dollars. However, the cost of the resulting water was $2.6 per cubic meter, five times more expensive than seawater desalination, due to the high costs of disposing of saline waste (residual brine). Unlike seawater desalination, where waste can be returned to the ocean with relatively low impact if done correctly, in indoor plants there is no simple option to dispose of brine. The CV Salts program’s original plan called for building a 450-kilometer pipeline to transport the brine to the ocean in San Francisco Bay, making the process drastically more expensive. To make the desalination of groundwater inland more viable, researchers are exploring brine valorization, i.e. converting this waste into useful chemicals for industry. An example of this is the work of New Mexico State University, where processes are being developed to separate the components of the brine and produce substances such as sulfuric acid and sodium hydroxide (caustic soda). These products are widely used in industry, from water treatment to battery and chemical manufacturing. If this process is made economically viable, not only will the cost of desalination in inland areas be reduced, but it will also be possible to generate a market for the by-products of desalination, making the process more sustainable and profitable.

Sedlak stresses that this is one of the most promising lines of research today, since it would allow desalination to be expanded to regions far from the sea without generating significant environmental impacts. In addition, if brine valorisation is implemented on a large scale, it could completely change the cost model of desalination in inland areas.

Reuse of drinking water: a solution already in place

Another key strategy in water management is the reuse of treated wastewater for human consumption. Although this practice still faces regulatory and public perception barriers, cities such as Singapore, Los Angeles, and San Diego have successfully implemented indirect and direct drinking water reuse programs.

A prominent example is the Aquifer Recharge System in Orange County, California, which treats 280,000 cubic meters of wastewater per day using reverse osmosis and advanced oxidation. This system allows the purified water to be returned to the aquifers, where it is later reused for urban supply. The cost of production is approximately $0.70 per cubic meter, making it a competitive option over desalination.

In the future, cities like San Diego and Los Angeles plan to reuse 100% of their wastewater, eliminating ocean discharge entirely. This trend is also gaining traction in Europe, with projects such as the one proposed in Barcelona.

Water Harvesting in Buildings and Communities

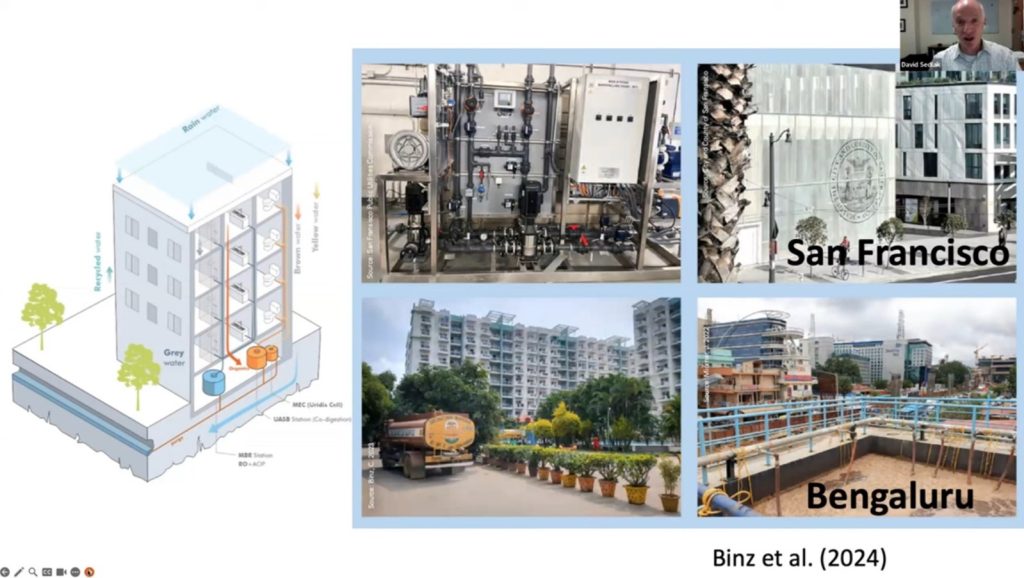

The water management model is evolving towards decentralised approaches, where urban infrastructures themselves can become water sources. Cities with scarcity problems, such as Bangalore and San Francisco, are promoting building-level water collection and treatment systems, allowing for immediate reuse.

Sedlak explains that advances in filtration and purification have made it possible for even recycled water inside a building to be used for human consumption. In India, these systems are enabling water self-sufficiency for some communities, reducing their dependence on external sources. According to Sedlak, these systems can pay for themselves in less than 10 years thanks to savings on the water bill.

Source: webinar with David Sedlak

Desalination, reuse and decentralised collection must complement each other to ensure a secure and sustainable supply in the long term. In addition, the development of more efficient technologies and innovative business models will facilitate the adoption of these solutions on a large scale.

In the coming years, the success of these approaches will depend on both technological advances and public acceptance and regulatory backing. Cities such as Los Angeles and Singapore have shown that good communication and transparent policies can build trust in recycled water, paving the way for its implementation in other regions.

Redesigning Water Infrastructure: Adapting Cities to Climate Change

Climate change is altering rainfall patterns around the world, intensifying both periods of drought and episodes of torrential rainfall.

David Sedlak points out that traditional water infrastructures, based on large reservoirs, dams and distribution channels, are no longer sufficient to manage these extreme weather events. The solution is not to build more dams, but to

Water Harvesting and Storage in Cities

One of the most promising approaches to improving water resilience is the recharge of aquifers through the use of rainwater. In regions with short rainy seasons and heavy rainfall, such as California and Spain, large volumes of water are lost and not stored. The key is to redirect these rains into underground aquifers instead of letting them flow uncontrollably.

In California, the program of aquifer recharge through controlled flooding in agricultural fields has proven to be an effective solution. During the rainy season, farmers allow their land to be flooded temporarily, which facilitates the infiltration of water into the subsoil. This measure helps to replenish groundwater reserves while reducing the risk of flooding.

This concept is also being explored in urban environments. Los Angeles is developing green infrastructure projects to capture and filter stormwater before it is lost to the ocean. One example is the project in Sun Valley, where artificial wetlands and infiltration ponds are being built to capture rainwater and recharge urban aquifers.

Source: webinar with David Sedlak

Cities have traditionally designed their drainage systems to evacuate water as quickly as possible, channeling it into rivers or the sea. However, this approach exacerbates water scarcity by not allowing water to infiltrate the soil.

Sedlak points out that in places like India, where monsoon rains have been a constant throughout history, water collection and storage systems were developed centuries ago, such as stepwells and infiltration galleries. These infrastructures, practically forgotten in the modern era, could be recovered and integrated into today’s cities.

Another innovative approach is the implementation of sustainable urban drainage systems (SUDS), including:

- Rain gardens that absorb stormwater and reduce surface runoff.

- Permeable pavements, which allow rainwater to infiltrate the ground instead of running down the streets.

- Underground tanks, which store rainwater for reuse in irrigation or non-potable consumption.

In the Netherlands, where flooding has historically been a problem, floodable squares are being developed, which function like parks under normal conditions, but can fill with water during intense storms, thus preventing streets and homes from flooding.

One of the biggest challenges in water management is that, although there are heavy rains, they do not always occur in the right places and at the right times. Infrastructure must be adapted to maximise the storage of available water. An example of this approach is the modernization of reservoir management in Spain and California. Instead of maintaining a system of rigid reservoirs, predictive models based on artificial intelligence and climate data are beginning to be used. This allows rainfall to be anticipated and storage to be optimized, ensuring that there is sufficient capacity in the dams when storms occur, and at the same time maximizing water capture during droughts.

On the Colorado River, which supplies water to much of the southwestern U.S., reservoirs have lost more than half their capacity in recent decades due to evaporation and poor resource management. In these cases, aquifer recharge is a more effective alternative to simply building more reservoirs.

The key to the future of water in cities is not to choose between traditional infrastructure or nature-based solutions, but to combine the two intelligently.

The cities of the future will need to integrate sustainable urban drainage systems, aquifer recharge and advanced technologies to improve water resilience. This hybrid approach will make it possible to adapt to climate change, creating more sustainable and water-efficient urban environments.

With investments in modernization, technological innovation and adaptation of existing infrastructures, it is possible to transform our cities into more resilient, efficient and sustainable water management models.

Questions and Answers (Q&A)

In the final part of the webinar, attendees were able to ask their questions to David Sedlak. These were some of the most relevant issues:

1. How to balance technological innovation with social equity and ecological resilience?

Sedlak emphasizes that solutions must be integrated into a framework of effective governance and integrated water management. Technology is key, but without inclusive policies and adequate regulations, it will not be enough to ensure equitable access to water.

2. What are the key emerging technologies in urban water management?

Reverse osmosis membranes have revolutionized desalination and the reuse of drinking water. In addition, the use of nature-based infrastructures and the optimization of water resources through AI are changing the paradigm of water management.

3. Is it feasible to manufacture water on an industrial scale in the future?

While atmospheric water harvesting or hydrogen generation are possibilities, Sedlak notes that desalination and reuse will remain the most accessible and scalable options.

4. How to increase public acceptance of recycled water?

The key is transparency and education. Pioneering cities have achieved public acceptance by showcasing the treatment process and allowing citizens to taste recycled water. In Singapore and Orange County, recycled water is bottled and distributed to the public to prove that its quality is equal to or superior to conventional bottled water. “If people try it and see that it’s the same as bottled water, it changes their perception,” says Sedlak.

Next event: Innovation for water sustainability

The Bankinter Innovation Foundation’s cycle of webinars on water continues on 27 February with the event Water Sustainability: Technological Solutions for the Future. On this occasion, success stories of two Spanish companies will be presented:

- GENAQ, which develops technologies to generate drinking water from the air.

- Jeanologia, a pioneer in reducing water use in the textile industry through clean technologies.

If you are interested in the future of water and the most innovative solutions, don’t miss this new meeting. Sign up and continue exploring how technology and innovation are transforming water management.