AI-generated summary

Silicon is a fundamental material underpinning the global digital economy, forming the base for semiconductor chips essential to smartphones, electric vehicles, data centers, telecommunications, and automation systems. By 2025, silicon’s significance extends beyond technology, becoming a strategic asset in industry and geopolitics. Its unique semiconductor properties—capable of acting as both an insulator and conductor—make it indispensable for modern electronics. Silicon’s abundance, stability, and compatibility with large-scale manufacturing have cemented its dominance in microelectronics, despite the emergence of alternative materials for niche applications.

The semiconductor manufacturing process is highly complex, requiring extreme precision and massive investment, which limits production to a few leading companies like TSMC, Intel, and Samsung. This concentration has geopolitical implications, with the U.S., China, and Taiwan playing pivotal roles, while Europe seeks to reduce dependency through targeted industrial policies. The 2020s chip shortage highlighted silicon’s critical role as disruptions affected multiple sectors, especially automotive and consumer electronics. Although emerging materials like germanium, silicon carbide, and gallium nitride complement silicon’s capabilities, silicon remains the core foundation of the semiconductor industry. To maintain competitiveness, Europe must enhance investment, develop talent, and foster partnerships to build resilient, sovereign semiconductor ecosystems, ensuring technological autonomy and economic security in the evolving global landscape.

Silicon, the basis of semiconductors, drives the digital economy and technological geopolitics. Industrial and strategic keys for Europe.

Silicon is one of the material pillars of the digital economy. On this element are built the chips that make computing, connectivity and automation possible on a global scale. Smartphones, electric vehicles, telecommunications networks or data centers share the same physical base: silicon.

By 2025, its relevance transcends the technological field. Silicon has become a strategic issue for industry and for geopolitics. This was highlighted at the Future Trends Forum held in December 2025, which focused on semiconductors as critical infrastructure for Europe’s economic competitiveness and technological sovereignty.

What is silicon and what is it for?

Silicon is a naturally occurring chemical element and one of the most important materials in the modern world. It is present in the sand, in the rocks… and in almost all the technology we use every day.

Their value is in their physical properties. Silicon is a semiconductor: it can behave as an insulator or as an electrical conductor depending on how it is modified. This capability makes it the basis of electronic chips.

In simple terms: without silicon there would be no computers, smartphones or the Internet.

What is silicon used for today?

Silicon is the core material of the semiconductor industry. From it, the transistors that form the chips are manufactured. These chips are in:

- Smartphones and computers

- Data Centers and Cloud Computing

- Electric vehicles and advanced driving systems

- Telecommunications networks

- Industrial Equipment Automation Systems

That is why, when we talk about silicon, we are talking about technology and, also, about economics, industry and geopolitics.

Why silicon? The material basis of the technological revolution

Although there are other semiconductor materials, silicon has become the standard in microelectronics for a combination that is difficult to match. It is abundant in nature, stable and reliable in the long term, and enables large-scale industrial manufacturing with contained costs. Added to this are decades of accumulated technological development, which have consolidated a unique industrial ecosystem.

From a physical point of view, silicon belongs to a very specific category of materials: semiconductors. Its electrical behavior can be fine-tuned by mature industrial processes, such as doping, allowing the flow of electrons to be controlled and transistors to be mass-produced. This ability to “program” matter is the basis of all modern microelectronics.

Unlike other semiconductors, silicon combines this electronic versatility with high thermal stability and full compatibility with extremely complex industrial processes. As a result, it has been possible for decades to integrate billions of transistors on a single chip with minimal failure rates.

The result is that silicon is not just a technological material, but the physical platform on which the digital economy is built. Although alternative materials are being explored for specific applications today, silicon remains the starting point for the entire semiconductor industry.

Silicon History: From Bell Labs to the Digital Economy

The turning point in the history of silicon occurred in 1947, with the invention of the transistor at Bell Labs. This breakthrough marks the beginning of modern electronics and paves the way for the miniaturization of devices. In the following years, silicon displaced germanium and consolidated itself as the reference material for the manufacture of semiconductors.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the integration of an increasing number of transistors into a single circuit gave rise to the microprocessor. This technological leap drives the birth of a new industry and a business ecosystem concentrated in California. Silicon Valley thus emerges directly linked to the material that underpins this transformation.

Since then, silicon has accompanied every stage of digitalization. Moore’s Law has guided the continuous improvement of chip performance for decades, multiplying computing power and reducing costs. In the 21st century, silicon becomes a cross-cutting enabler of the digital economy: cloud computing, artificial intelligence, electric mobility, telecommunications networks, and advanced industrial systems.

Today, silicon is close to its physical limits, which has driven new architectures, advanced manufacturing techniques, and the incorporation of complementary materials. Still, it remains the foundation on which global technology infrastructure is built and the starting point for the next phase of the semiconductor industry.

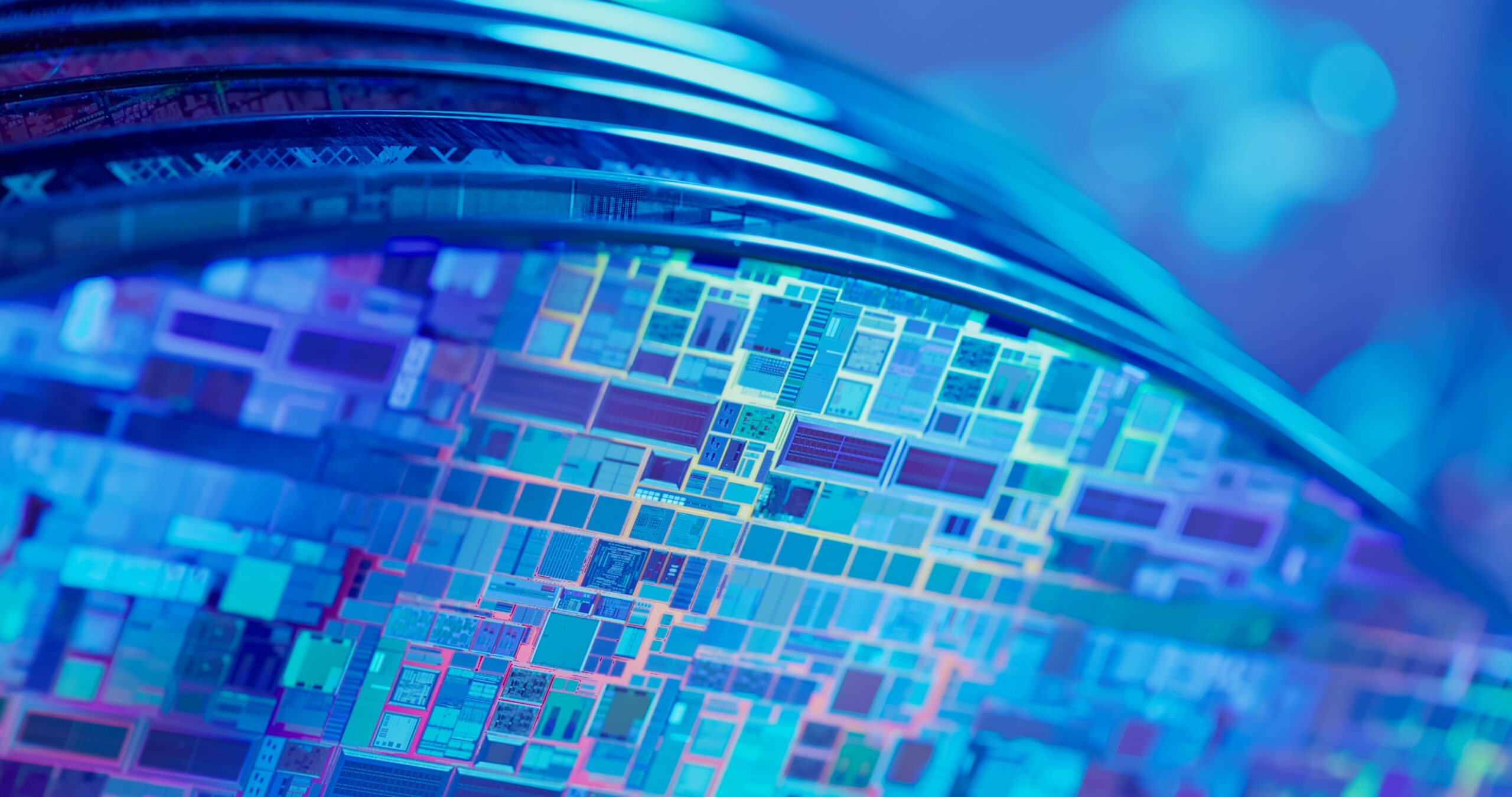

The manufacturing process: from sand to wafer

The transformation of silicon into a chip is one of the most complex and demanding industrial processes that exist. It combines chemistry, physics, materials engineering and extreme automation.

The starting point is purification. Silicon of the highest purity, greater than 99.99999999% is obtained from quartz sand. This level is essential to guarantee the electrical behaviour of the material.

This is followed by the growth of the crystal. Using the Czochralski process, the molten silicon solidifies into a monocrystalline ingot, with a perfectly ordered atomic structure.

That ingot is then cut into wafers. Extremely thin discs, the wafers, are obtained and polished to an almost perfect surface.

The chip is manufactured on each wafer. Through successive phases of lithography, deposition and etching, microscopic layers are built that house billions of transistors, with precisions measured in nanometers.

The process ends with the test and encapsulation. Each chip is individually verified before being integrated into a package that protects it and allows it to be connected to the rest of the system.

In this environment, fault tolerance is minimal. A failure in any of the stages can render the entire wafer unusable, which explains the high level of specialization, investment, and control that characterizes the semiconductor industry.

Why Chipmaking Is So Difficult and So Strategic

Semiconductor manufacturing concentrates some of the largest industrial barriers that exist today. It requires multi-million dollar investments, long development cycles and a level of technical precision that only a few players in the world can achieve.

Each advanced chip factory integrates thousands of processes, highly specialized equipment, and global supply chains. The coordination between materials, machinery, software and scientific knowledge is critical. The margin for error is minimal and the costs of failure are very high. This level of complexity naturally limits the number of companies and countries capable of competing at the technological frontier, as we will see in the next section.

Added to this technical difficulty is a strategic dimension. Semiconductors are a cross-cutting input for key sectors such as automotive, energy, telecommunications, defence and artificial intelligence. External dependence on its supply exposes entire economies to industrial and geopolitical risks.

For this reason, the ability to manufacture chips has become a strategic asset. Governments and regions are competing to attract investment, ensure access to critical technology and strengthen their industrial autonomy. In this context, silicon is no longer just a material but becomes part of the economic and strategic infrastructure of the 21st century.

The chip giants: the role of TSMC, Intel and Samsung

Advanced semiconductor manufacturing is one of the most concentrated industrial segments in the world. Although silicon is abundant, the ability to transform it into state-of-the-art chips is in the hands of a very small number of players.

TSMC leads the industry on a global scale. The Taiwanese company dominates the most advanced technological nodes and manufactures chips for many of the companies that define the digital economy, including Apple, NVIDIA and AMD. Its position is critical for sectors such as high-performance computing and artificial intelligence.

Intel, a historical pioneer of microelectronics, maintains a relevant position in both design and manufacturing. In recent years, it has initiated a strategy of strong investment to regain technological leadership, with new plants in the United States and Europe and a model that combines its own production and manufacturing services for third parties.

Samsung Electronics occupies a unique position. It is a world leader in memory and one of the few players capable of producing advanced logic chips on a large scale. This dual strength allows it to compete in different key segments of the value chain.

As the Future Trends Forum highlighted, Europe is critically dependent on this external capacity to supply its industry. This dependence explains the drive for new industrial policies aimed at strengthening local semiconductor production and reducing vulnerabilities in an area considered strategic.

The geopolitics of semiconductors: the new “oil” of the 21st century

By 2025, silicon has established itself as a power asset. The ability to manufacture advanced semiconductors conditions the development of the digital economy, defense, critical infrastructures, and the energy transition. The control of this technology has become a determining factor of competitiveness and strategic autonomy.

The current global balance is defined by three main axes: the technological rivalry between the United States and China, Taiwan’s centrality in advanced manufacturing, and Europe’s reaction to its external dependence. In this context, the European Union has activated industrial policies aimed at attracting state-of-the-art factories, strengthening the supply chain and reducing vulnerabilities.

As the Future Trends Forum underlined, the debate goes beyond economic efficiency. The central issue is resilience: ensuring access to critical technology in an environment marked by geopolitical fragmentation and global uncertainty.

Economic Impact of Silicon Shortages: The Chip Crisis

The semiconductor crisis highlighted the systemic nature of silicon. A disruption in its supply was enough to simultaneously affect multiple industrial sectors and consumer markets around the world.

Effects on the automotive industry

The automotive industry was one of the most affected sectors. Factory stoppages, delivery delays and incomplete vehicles became a constant. A modern car integrates thousands of chips that control everything from engine management to assistance and safety systems. Without semiconductors, the production chain stops.

Effects on consumer electronics

Consumer electronics also suffered the consequences. Smartphones, consoles and computers registered delays in their launch and price increases. For months, demand exceeded available supply, highlighting the fragility of highly globalized supply chains optimized to the limit.

Silicon vs. Other Emerging Semiconductors

Silicon remains the dominant material in the semiconductor industry. The advancement of new applications and the physical limits of miniaturization have driven the development of alternative materials, each with specific advantages.

| Material | Key benefits | Limitations | Main Uses |

| Silicon (Si) | Scalable, cost-effective, mature industrial ecosystem | Physical limits in very advanced nodes | Logic chips and memory |

| Germanium (Ge) | High e-mobility | Lower thermal stability and lower industrial maturity | Research and niche applications |

| Silicon Carbide (SiC) | High energy efficiency, withstands high voltages and temperatures | High cost and complex manufacturing | Electric vehicle, power electronics, energy |

| Gallium nitride (GaN) | High frequency and high power density | More complex industrial integration | 5G, fast chargers, radar |

The consensus in the industry is clear. These materials expand the capabilities of silicon and make it possible to respond to new needs, especially in power, efficiency and communications. In the short and medium term, their role is complementary. Silicon will continue to be the foundation of global microelectronics, supported by other semiconductors in specific applications.

To delve into this evolution of the materials ecosystem, we recommend Ana Cremades‘ presentation, “Beyond Silicon: Expanding the Materials Palette for Microelectronics“, where she analyzes how materials diversification will be key to the next stage of the semiconductor industry:

Strategic conclusion

The semiconductor industry has ceased to be a specialized industrial activity and has become an essential infrastructure of the global economy. The last Future Trends Forum, held in December 2025, highlighted two realities that condition the competitiveness of Europe and Spain: the profound transformation of the chip value chain and the geographical and technological concentration of their manufacture.

Global demand for semiconductors is growing exponentially, driven by artificial intelligence, electric mobility, data centers, and industrial automation. This growth requires more productive capacity and a greater diversity of products and technologies. Europe has industrial capabilities in segments such as power electronics, sensors and microcontrollers, but still relies on advanced manufacturing capabilities concentrated outside its borders.

The discussions at the Future Trends Forum underscore that competing on this new global chessboard requires a comprehensive strategy. It is necessary to:

- Increase public and private investment to attract and consolidate competitive design and manufacturing infrastructures.

- Strengthen specialized talent at all levels of the technology chain.

- Boost smart specialisation in areas where Europe has clear advantages, such as packaging, sensors, power and architectures geared towards industrial use cases.

- Foster public-private partnerships and regional value chains, integrating SMEs, research centres and large companies to create sustainable and resilient ecosystems.

These levers will strengthen industrial capacity and contribute to technological autonomy and economic security in an increasingly competitive global environment.

The race for silicon is one of the great technological and economic battles of the 21st century. Europe still has time and opportunities to position itself, provided it acts in a coherent and coordinated way.

Profesor del Departamento de Física de Materiales de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid.